Bruno Miguel: Seduction and Reason

September 29 - November 5, 2017;

Preview September 28 and Opening on September 29, 6-8pm

Essay by Aliza Edelman, Ph.D.

From the delirious reverberations of Os Mutantes’ deadpan reprise, “Essas pessoas na sala de jantar / São ocupadas em nascer e morrer” (These people in the dining room / are busy being born and dying), the undercurrents of Tropicália’s musical and artistic experimentalism surged. The song, with lyrics by musicians Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, and Rogério Duprat’s arrangement, was first performed by the Brazilian band in 1968 at the Festival International da Canção, in Rio, and soon thereafter revered in the multi-artist album Tropicália: ou panis et circencis (Bread and Circus), drawn from the soundtrack’s title. The song’s frenetic accumulation, a postwar mantra exposing bourgeois complacency amid the country’s military oppression and censorship, culminates in rattling glass. The all-encompassing sounds of the late sixties in Brazil turned synchronously to psychedelic rock, bossa nova, samba, and northeastern Bahian music. Postwar artists identified with New Figuration and Pop, such as Hélio Oiticica, Antonio Dias, Rubens Gerchman, and Cildo Meireles, among many others, mirrored this desire to consume or cannibalize cultural modes and foreign influences in the crystallization of an autonomously Brazilian identity. This anthropophagic gesture, originally advanced by modernist poet Oswald de Andrade in the 1920s, was thus revitalized with new purpose.[1]

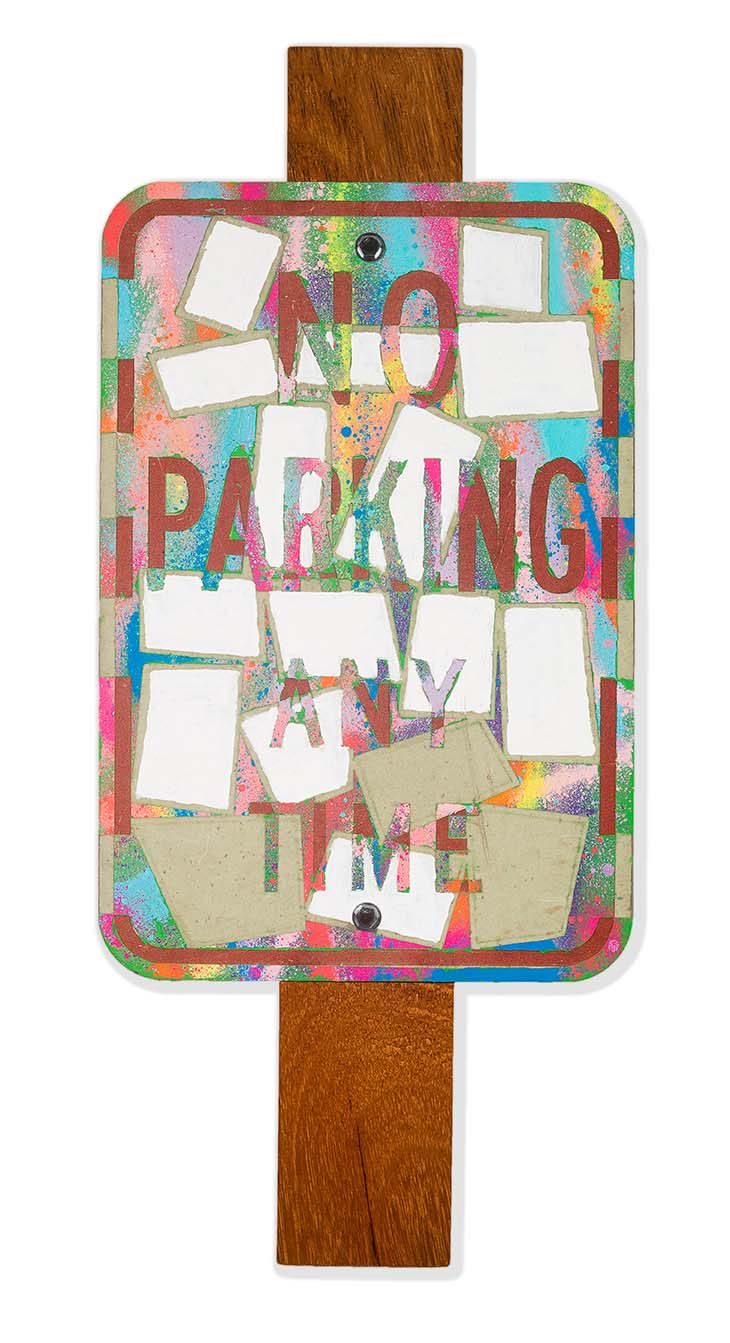

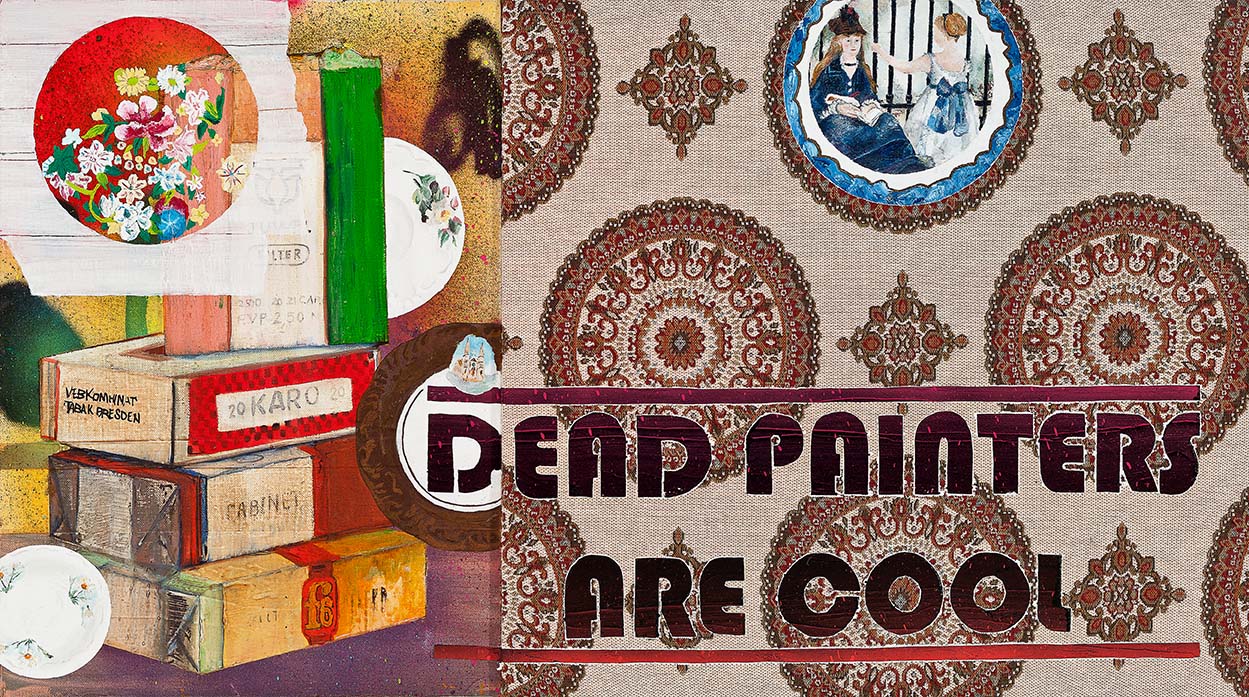

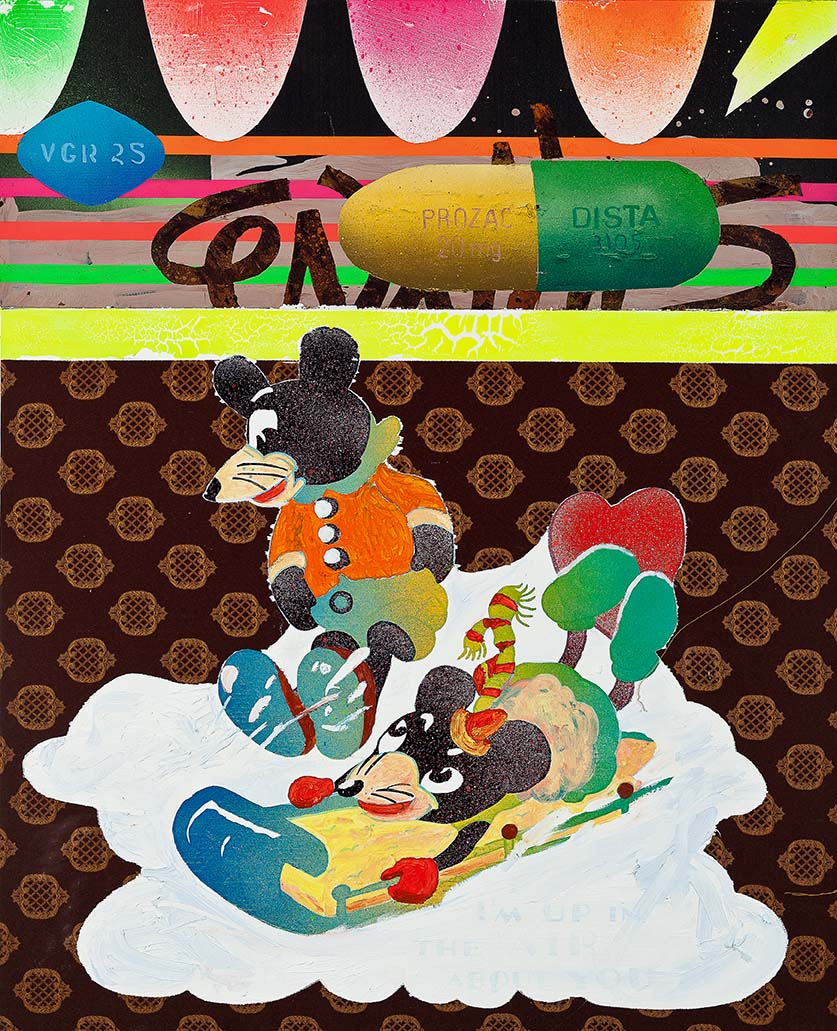

Seduction and Reason reveals Bruno Miguel’s playfully irreverent appropriations of Brazil’s layered histories. Influenced by the extraordinary traditions of Tropicália and postwar Pop, Miguel’s varied series explore the fluid narratives between past and present, high and low, and private and public. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1981, Miguel draws his subjects from the seductive pull of popular culture’s consumer brands, billboards, and advertisements, American postwar vernacular (and its infiltration in Latin America), and the country’s deeply rooted colonial past. Likewise, he stresses our proclivity for technology and social networks. An obsessive collector of quotidian objects amassed at auction and antique stores, Miguel stockpiles porcelain dinnerware, table napkins, crystal, textiles, soda bottles, glasses, books, and toys. His series incorporate these objects as “witnesses” of a lived history, stimulating in their “intimate relationships” and “meaningful differences” an organic direction for the work’s development.[2

A first-generation Brazilian (his mother was from Mozambique and father from Portugal), Miguel counters traditional ways of visualizing Rio de Janeiro’s mythic landscape, an approach informed by his daily commute into the city’s wealthy Zona Sul from the peripheral suburbs of Ilha do Governador in the Zona Norte.[3] In his expansive series Essas Pessoas na Sala de Jantar (These People in the Dining Room) (2012-15), Miguel creates an immersive environment of fantastical trees and sinuous mountains in garish colors from which decorative porcelain plates, cups, tureens, saucers, and tea pots emerge. Surfaces are layered fastidiously in polyurethane foam, resin, wire and papier-mâché, experimenting adeptly with traditional techniques employed in Carnival. Taking its title from Os Mutantes’ hypnotic lyrics, the works’ amorphous forms and erratic presentation embody the landscape’s transmutation: Rio de Janeiro is readily consumed and devoured in its own simulacrum or artificial representation. In its collective display as an ornamental confection of porcelain and hardened foam, These People in the Dining Room is a baroque yet atrophied garden continually regurgitating its history as a haphazard germination of trees and plants. As singular sculptures, however, the artist positions them as manifestations of the domestic realm, granted personal names, and offered as the bearers of individual “silent testimonies.” Porcelain or precious china, often reserved for special occasion, is thus a repository for memories and also a metaphor of something unattainable. As objects placed on the floor to negotiate, they are likewise a proposal and reminder to the viewer to live in the present.

The related series A Cristaleira (Crystal Cabinet) of 2015 is similarly a vast collection of individual Compositions (Composiçoēs) arranged in groups or in multiple “conversations.” Recalling elegant crystal carefully stored in hutches or cabinets, the vertical assemblages of prosaic and informal glasses, vessels, and molds are filled with chromatic resin layers to undermine their ostensibly luxurious provenance. Squat, phallic, svelte and bulbous, A Cristaleira’s translucent resin strata are Miguel’s still-life “protagonists.”

Invariably, Miguel’s studio practice reflects how both personal and popular artifacts are carried with us as an inheritance embellishing our imaginary landscape. This topography of the home irrevocably influences and determines the direction of Miguel’s research. Miguel offers, “The studio steals from the home and vice versa, but always in a very harmonious way.”[4] Cafezinho? (2014) elicits his mother’s homemaking in its familial and welcoming question, Coffee? Understood as a portrait of his mother, the simple display of thirty-one brightly filled Tupperware cups calls upon our sense of nostalgia, a memory induced longing, estrangement and affection that no longer exists, as identified by historian Svetlana Boym.[5] In homage to his father, three modest shot glasses holding red, blue, and yellow resin are a curt expression of patriarchal lineage.

Miguel’s Seduction and Reason is the artist’s bricolage, an indefatigably “savage” shaping of materials for new meaning and “mythical” purpose, which in his case appears to resist scientific reason and permanence.[6] Fé (Faith) (2013), from the series Sala de Jantar (Dining Room), is thus a visual feast of optical and ornamental surfaces. Fifty-four vintage and common porcelain and faience plates of various shapes (for example, Villeroy & Boch, France-Germany; Gilman & Cia, Portugal, Porcelana Steatita, Brazil) are meticulously refashioned and emblazoned in oil and enamel: in one, a provincial view of Rio de Janeiro’s resplendent Pão de Açúcar is painted as a platter and activated with geometric chevrons and vibrant cross-hatchings to decorate an authentic platter; in another, modestly drawn wildflowers adorn an exquisite saucer of cobalt floral scrolls; for others, styrofoam displaces porcelain as a witty trompe-l’oeil effect. Moreover, the gestural application of paint in swatches and wide colorful swathes unifies the work’s potential as a holistic abstraction, an allusion to graffiti and sprawling billboards traversing the urban landscape. Miguel’s self-proclaimed identification as a painter magnifies these relationships between excess and rigor and domestic and professional space.

It is in fact through the circulation of objects imbued with personal ownership—luxurious and kitsch, fractured and intact—that Miguel finds potential for experimentation. Ouro (Gold) is a decorative cup filled to the brim with “gold tea.” The cup is an example of historic Companhia das Índias, the Chinese export porcelain popularly manufactured and distributed on demand for both the courts and masses in the Portuguese and European markets, from the sixteenth to early twentieth-century. In its simple stature, however, the teacup evokes ambitious colonial trade routes and global monopolies; as a seductive vessel, moreover, it reflects in its splendor Bruno Miguel’s vast universe that rests uneasily on the edge of painting.

Aliza Edelman, Ph.D., is a curator and art historian focusing on the transnational narratives of postwar and contemporary artists in the Americas. In 2014 and 2017, she organized surveys on the Brazilian Concrete painter, Judith Lauand. Current scholarly writings are included in Women of Abstract Expressionism (Yale Univ. Press and Denver Art Museum) and American Women Artists, 1935-1970 — Gender, Culture, and Politics (Routledge), both 2016.

[1] See Oswald de Andrade, “Manifesto Antropofágico,” Revista de Antropofagia 1 (May 1928).

[2] Bruno Miguel, correspondence with the author, 14 September 2017.

[3] See Monica Espinel, “Todos à Mesa,” in Bruno Miguel: Todos À Mesa, exh. cat. (São Paulo: Galeria Emma Thomas, 2014), n.p.

[4] Miguel, correspondence with the author, 14 September 2017.

[5] On nostalgia, see Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001).

[6] In the 1960s, the French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss proposed the controversial concept of bricolage in The Savage Mind (Chicago: The Univ. of Chicago Press, 1966), 35-36.

About Bruno Miguel

Bruno Miguel (b. 1981) lives and works in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An inveterate collector of quotidian objects, Miguel’s practice explores the fluid relationships and personal stories embedded in familiar household items and consumer products to reframe the international dimensions of Pop Art and the avant-garde in Brazil. Miguel’s paintings and installations---which frequently manipulate traditional Carnival techniques in polyurethane foam, resin, and papier mache—convey the layered histories of Rio de Janeiro's landscape from a critical periphery.

He has had individual institutional exhibitions at Largo das Artes (2010), Museum Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2016), Centro Cultural da Caixa Econômica Federal, and Centro Cultural São Paulo (2016). His work was included in multiple editions of the Biennial of La Paz, Bolivia. In 2007, Miguel received an honorary mention at the V International Biennial of Art SIART in La Paz, Bolivia, followed by a fellowship from the Furnas Social-cultural for Artistic Talents. His work was included in group exhibitions at the Cultural Center Bank of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (2008 and 2009); Museum of Contemporary Art, Santiago, Chile (2010); Caixa Cultural, Rio de Janeiro (2011); Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ, 2012); Hélio Oiticica Art Center, Rio de Janeiro (2012); Museum of the Republic, Rio de Janeiro (2013); and Museum of Art, Rio de Janeiro (MAR-RJ, 2014).

In 2009, Miguel graduated in Fine Arts and Painting from the the School of Visual Arts, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Currently, he teaches art and art theory at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and at the School of Visual Arts, Parque Lage. He also curates Mais Pintura, a project and publication series dedicated to the emerging generation of Brazilian painters.