Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer: The Unicorn and Other Creatures of Hope

January 23, 2026 – February 21, 2026

Sapar Contemporary is pleased to announce their second solo exhibition of works by Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer (Italy). The Unicorn and Other Creatures of Hope is a new body of work where Ferrer turns her gaze to the unicorn — a creature whose mythology has traversed millennia, continents, and belief systems — as a vehicle for exploring ideas of liberty, captivity, purity, and transcendence. Drawing upon a decade-long fascination with The Unicorn Tapestries at The Met Cloisters, Ferrer reimagines the unicorn as a deeply spiritual being, a symbol both of sovereignty and sacrifice.

The Unicorn continues Ferrer’s exploration of ritual, mythology, and the sacred. Her paintings reinterpret Christian iconography through a universal lens. Living and working in Tuscany, Ferrer engages deeply with the Christian and pagan mythologies that saturate the European landscape. “Where before in my work there was melancholy, now there is mystery,” she reflects. “Where before there was tragedy, now there is a glimmer of hope.”

Emma Ferrer’s unicorns are no child’s plaything

by Katie White

In “The Unicorn and Other Creatures of Hope,” the artist’s second solo exhibition with Sapar Contemporary Art Gallery, Ferrer reimagines the mythical beast across two dozen new works. Rainbows and sparkles of a toy-store unicorn, these are not. Ferrer draws instead from the deep well of the medieval world and restores unicorns to their centuries-old roles as tragic, romantic symbols.

“Historically, the unicorn represents the apex of what the human imagination can conjure: beauty, power, purity,” Ferrer shared by phone from Camaiore in Tuscany, Italy, where she lives and works. “With the unicorn comes this desire to own, capture, and dominate it.”

Her latest series was sparked by a visit to the Unicorn Tapestries, a cycle of seven late Gothic tapestries depicting the hunt of the unicorn, on view at the Met Cloisters in Upper Manhattan. She’d first seen the tapestries nearly a decade before, but returning last winter, Ferrer found herself newly moved by the splendidly detailed scenes.

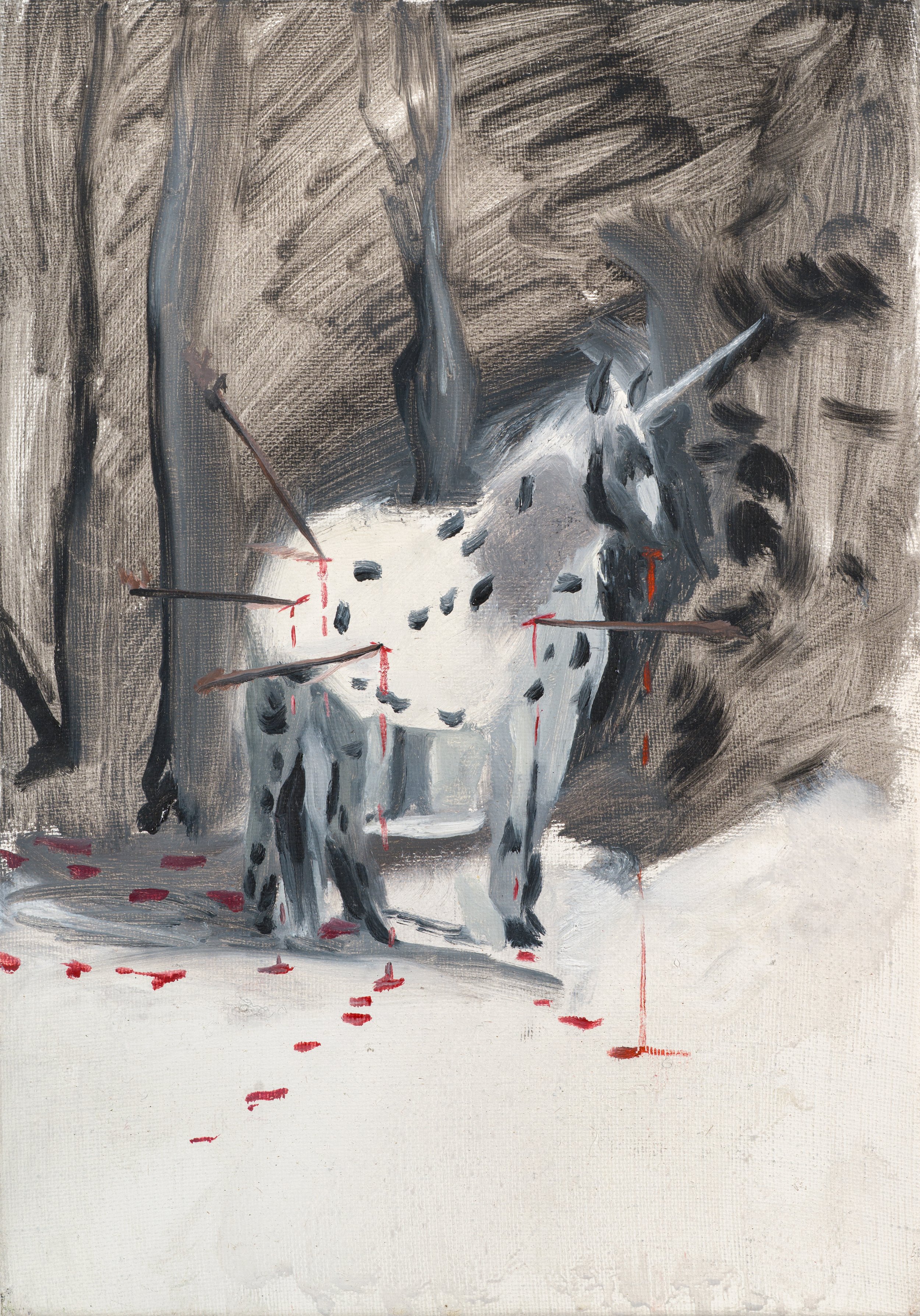

“I had an ‘Aha!’ moment seeing the tapestries again,” she recounted. In myth, the unicorn is pursued for its horn, which was believed to possess the ability to purify water. In the tapestries, the unicorn is chased through forests and streams, and battles off hunters and dogs, only to be tamed by a virgin and ultimately slain. However, in the final tapestry, as if by miracle, the unicorn appears alive once more, resting in a fenced-in garden.

“The whole cycle is incredible, but that iconic image, The Unicorn Rests in Captivity,, with pomegranate juice dripping down the unicorn…” she said, “It’s aesthetic and beautiful, and quite tragic.” Ferrer is drawn to the myth of the unicorn in part because it offers no clear ethical justice , no simple right and wrong. In one of the more gruesome scenes at the Cloisters a pack of hunting dogs tears into the unicorn; one gnawing his leg, the other sniffing his wound, and a third being impaled by the unicorn’s horn who desperately defends himself. A young girl who sat near Ferrer looking at the scene turned to her father and asked, “Is the unicorn stabbing the dog because the unicorn is bad, or because the dog is bad?” The question would return to the artist with vengeance over the next year.

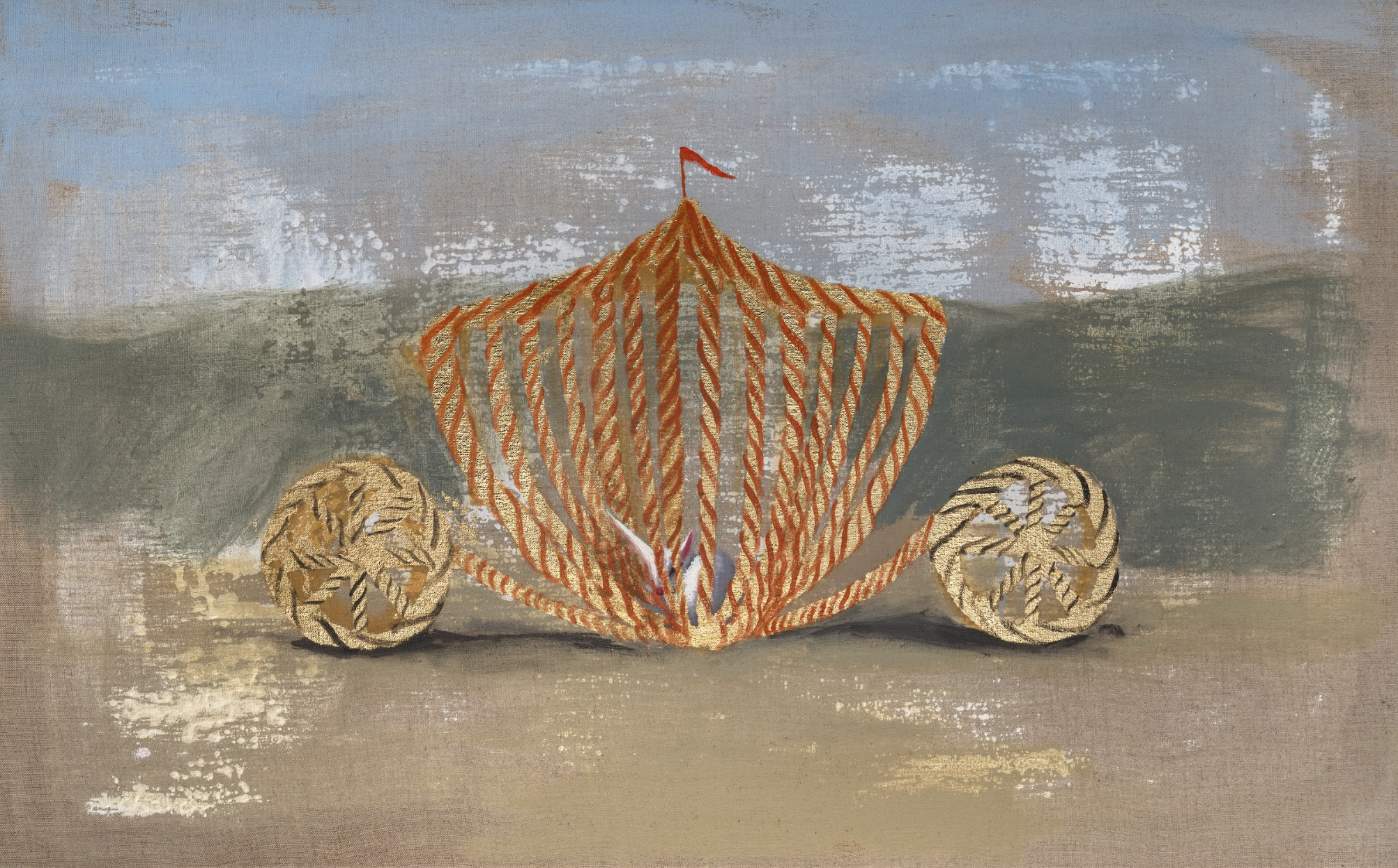

Her own visions revel in such nuance. In one work, Plaything (2025), she reimagines The Unicorn Rests in Captivity. Ferrer’s unicorn is hemmed in by a playpen, rather than a fence, and is surrounded by colorful toy balls, “as thoughsuch simple objects could placate the desire of such a wise and powerful being.” .

Ferrer’s new works can be understood as contemplations of spirituality and freedom in our unmoored era. Before earning her MFA at Central Saint Martins in 2024, Ferrer studied Greek mythology, history of theology, and philosophy of religion through SUNY and Harvard Extension School. These layered disciplines shape her artistic practice.

In her 2025 debut exhibition with Sapar Contemporary, Ferrer delved into the history of the Scapegoat, an ancient tradition in which a goat was symbolically imbued with the sins of a community, and subsequently sent into the wilderness to die, cleansing the community. Taking inspiration from Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt’s painting The Scapegoat (1854–1856) as well as Francisco de Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei (1640), Ferrer created a body of work mining the spiritual depths of sacrifice.

Ferrer now sees a connection between theScapegoat and the unicorn. “The unicorn and the scapegoat are ultimately consorts,” she considers. “They're two sides of the same coin where the goat embodies all of the suffering and shame and pain that we want to do away with, and the unicorn embodies everything that we want to appropriate and be—ultimate power, love, beauty, and purity. These are polar opposites,both extremes.”

In some of her new works, unicorns, goats, and lambs bleed together in chimerical unions. “Emma is leaning into the history of the unicorn, and in really early representations, it's unclear which animal the unicorn is meant to be,” said Nina Levent, co-founder of Sapar Contemporary.

In A King is Born (2025), a two-sided oil-on-wood work, for instance, a lamb appears with a unicorn's horn. On one side of the work, the lamb lies within a carriage in a majestic gold-leaf circus tent loosely inspired by the shape in Constantine’s Dream by Piero della Francesca. On the other side, the newborn lamb is held in a cage.

“The core question I kept returning to during the creation of these works is around the notion of captivity versus freedom.. Why do we want to put the unicorn in the cage?” Ferrer asks, “If we put something in a cage, who is really on the inside and who is really on the outside? Is it not us that’s in the cage?”

While these scenes are mythical, the implications are real-world. “Ultimately, the unicorn doesn’t exist, and the unicorn is pure and free. It can never truly be in a cage, but our desire for power, this ever-receding horizon of domination, cages us.”

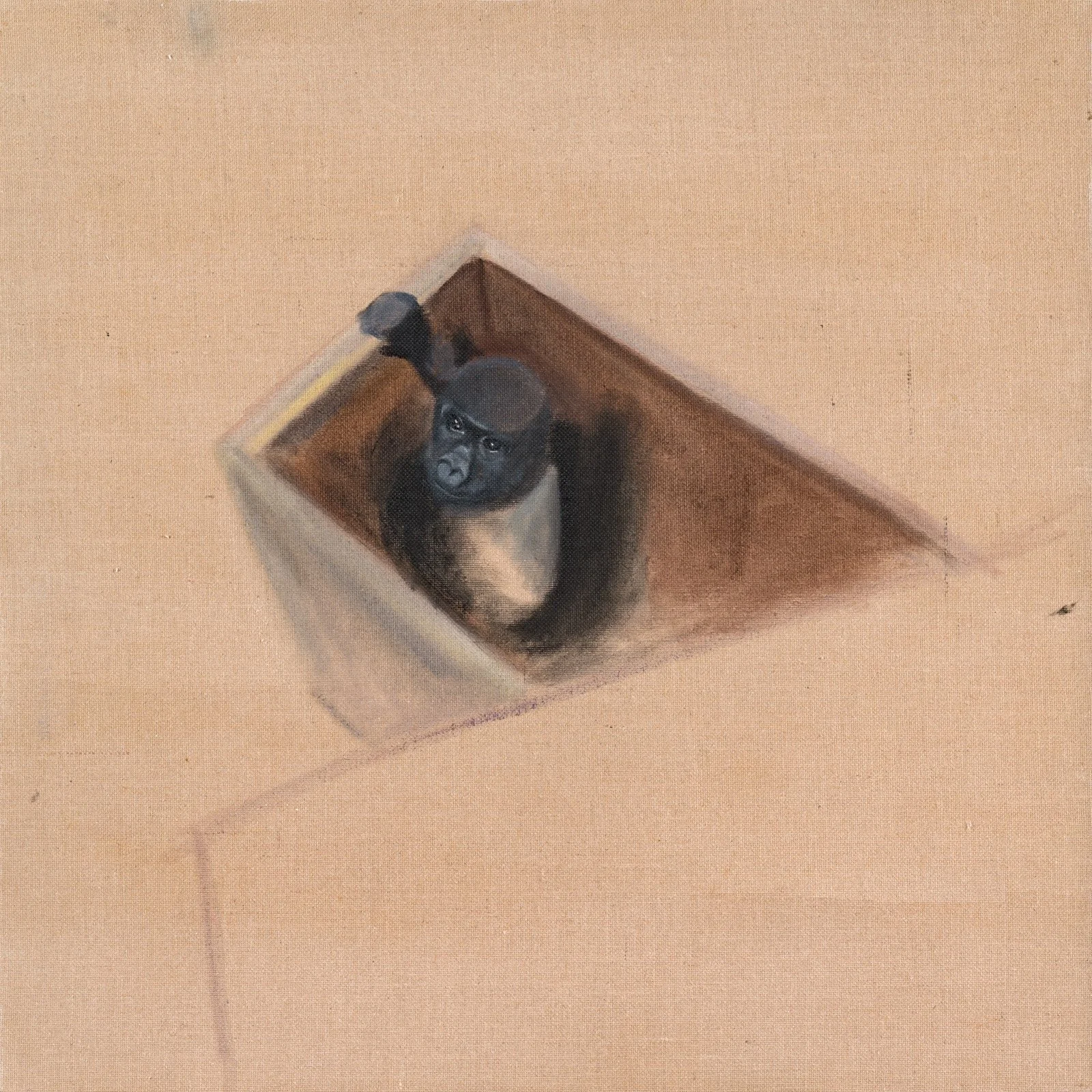

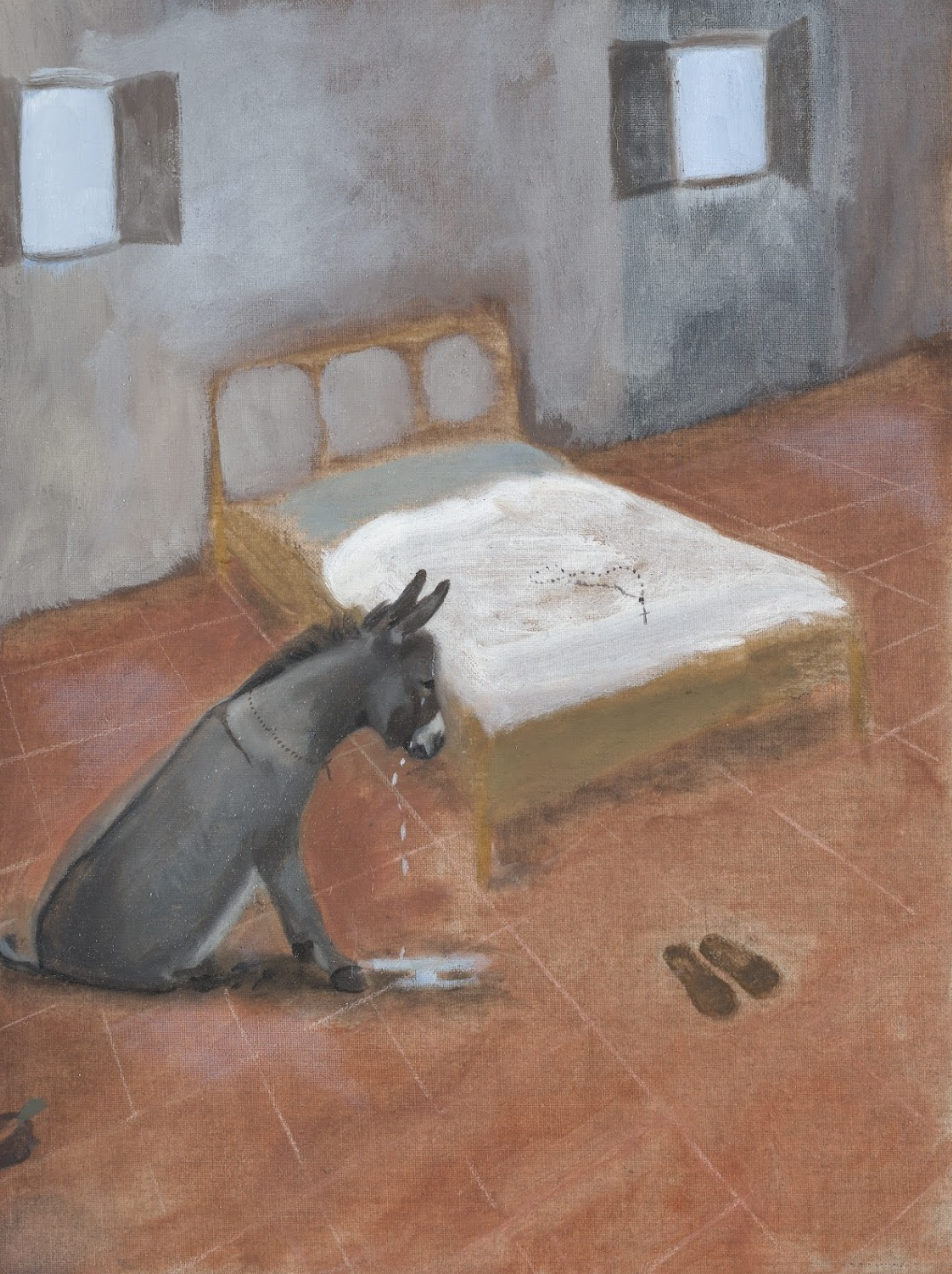

Still, these works feel peaceful, even hopeful, in moments. Ferrer’s backgrounds are spare and abstracted, with the frequent appearances of water and snow imbuing a sense of tranquility throughout the show. In moments, Ferrer’s imaginary world widens and other animals appear—a lone seal on the beach, a dark-eyed monkey, a weeping donkey mourning the beloved St Francis.

While the artist never set out to be a painter of animals, she sees them as symbols that allow us to contemplate complex truths. “Painting animals lets me use symbols, allegories, archetypes,” Ferrer explained, “They’re an effective way to ask people to think without being too upfront.” The artist’s remote life in Tuscany only further fuels these associations. “There is a connection between the mystical animal of our imagination and the actual animals that we live with,” Levent added, “Where Emma lives, she's surrounded by domesticated animals.”

The exhibition also marks an exciting new material chapter for the artist, who is debuting sculpture and print work for the first time. One sculpture, Unicorn Chasse (2026), features a long brass unicorn in a reliquary-like glass box, an object of devotion and spirituality. For the artist, expanding into three-dimensions was only a matter of time. “Nina has always pushed me to think about the devotional quality of objects,” said Ferrer, “How can actual objects become relics, tokens that help us access something spiritual or communicate with a concept of God?”

While Ferrer doesn’t hand over an answer, in her world of unicorns, she welcomes the pursuit.

About Artist

Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer was born in Morges, Switzerland and grew up in Florence, Italy surrounded by the works of medieval and Renaissance artists. As a young adult, Ferrer spent six years in New York where she maintained a studio practice whilst working in art galleries as a curator and artist liaison. In 2021 she returned to her home in Camaiore, Italy, devoting herself to her art practice. There, reflecting on the remote beauty of her rural environment, she began investigating a complex relationship between humans, animals, and Nature, and the relationship of these to a higher power.

Early in her artistic career Ferrer pursued a classical education in drawing and painting. One of the youngest students ever accepted into the academy, at 18 years of age Ferrer enrolled in the Advanced Painting program at the Florence Academy of Art, a traditional atelier where she would be imbued in the techniques, methodologies, and theories of the old masters. There, Ferrer undertook exhaustive studies from life including still life and the live figure, studying human anatomy as well as becoming fluent in classical materials in drawing, painting, and sculpture. While she initially honed in on an extremely naturalistic way of portraying reality, working solely from life, Ferrer over the last decade has looked inward, greatly loosening her style and leading with an emotive and intuitive practice.

Ferrer received her MFA from Central Saint Martins in London in 2024. Throughout the course of her education she has studied under and worked for artists such as Golucho and the maestro Ivan Theimer. She has curated the works of fashion designers Zac Posen and Manolo Blahnik, and artists such as Eugenio Pardini and Sofia Cacciapaglia. Ferrer holds significant admiration for the Quattrocento painters Piero della Francesca, Masaccio, and Paolo Uccello. As a young painter, Ferrer also spent extensive time in Spain where she discovered and investigated the works of Francisco de Zurbaràn, Symbolist painter Julìo Romero de Torres, and Goya.

About Writer

Katie White is a New York-based writer and editor for Artnet News. She frequently writes artist profiles and art historical analysis. Other passions include naming emergent trends in the art world and shining a light on artists overlooked by history. White has a master's degree in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where her thesis was supervised by Linda Nochlin. She has previously held positions at the Sotheby’s New York, SNAP editions, the Armory Show, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among other institutions.