Anya Zholud: An Intimate Portrait

Essay by Dr. Ksenia Nouril, Jensen Bryan Curator, The Print Center and specialist in Central and Eastern European Art

March 31, 2021 - May 1, 2021

Opening March 31 , 5-7 pm (we are welcoming groups under 8 people)

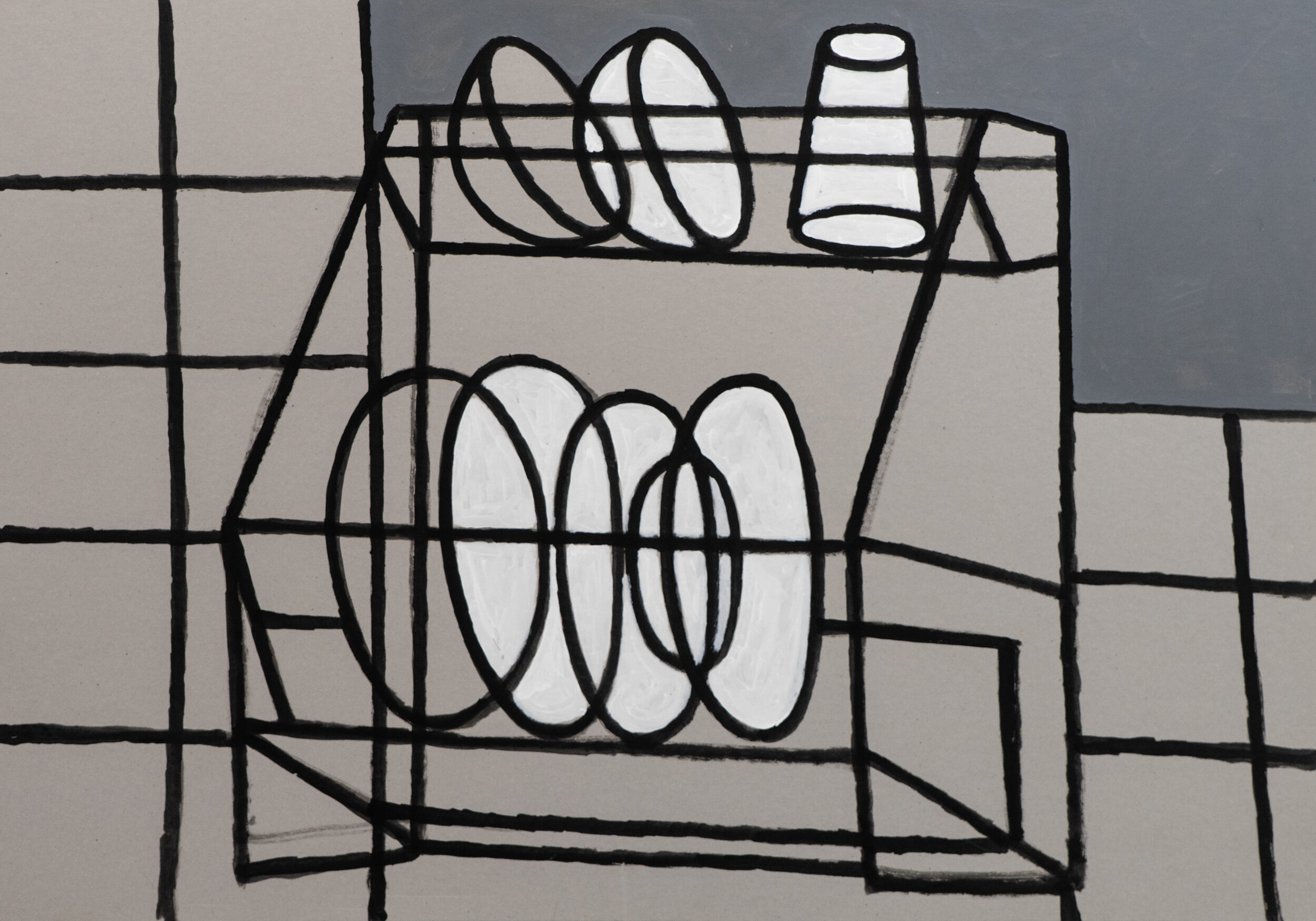

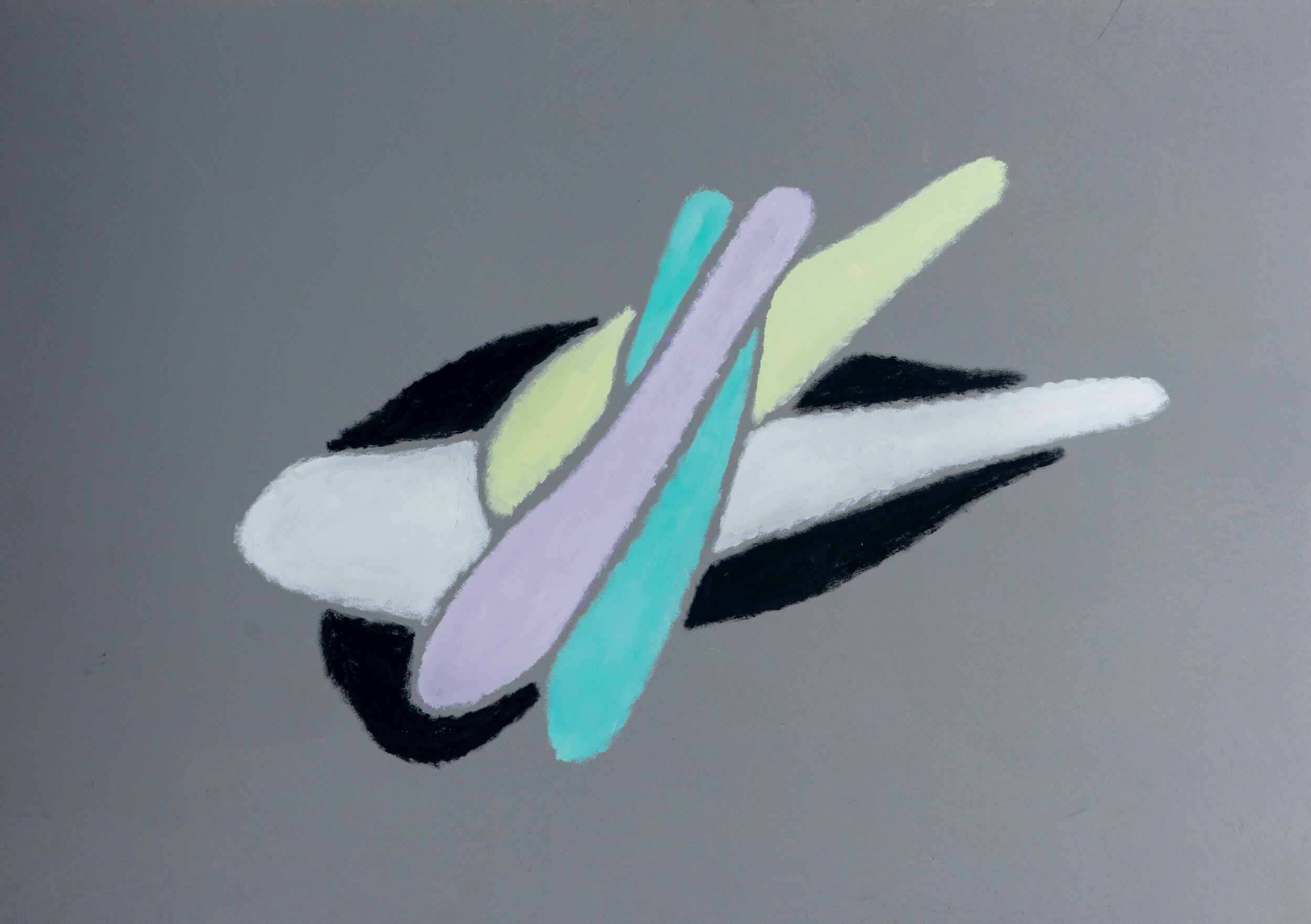

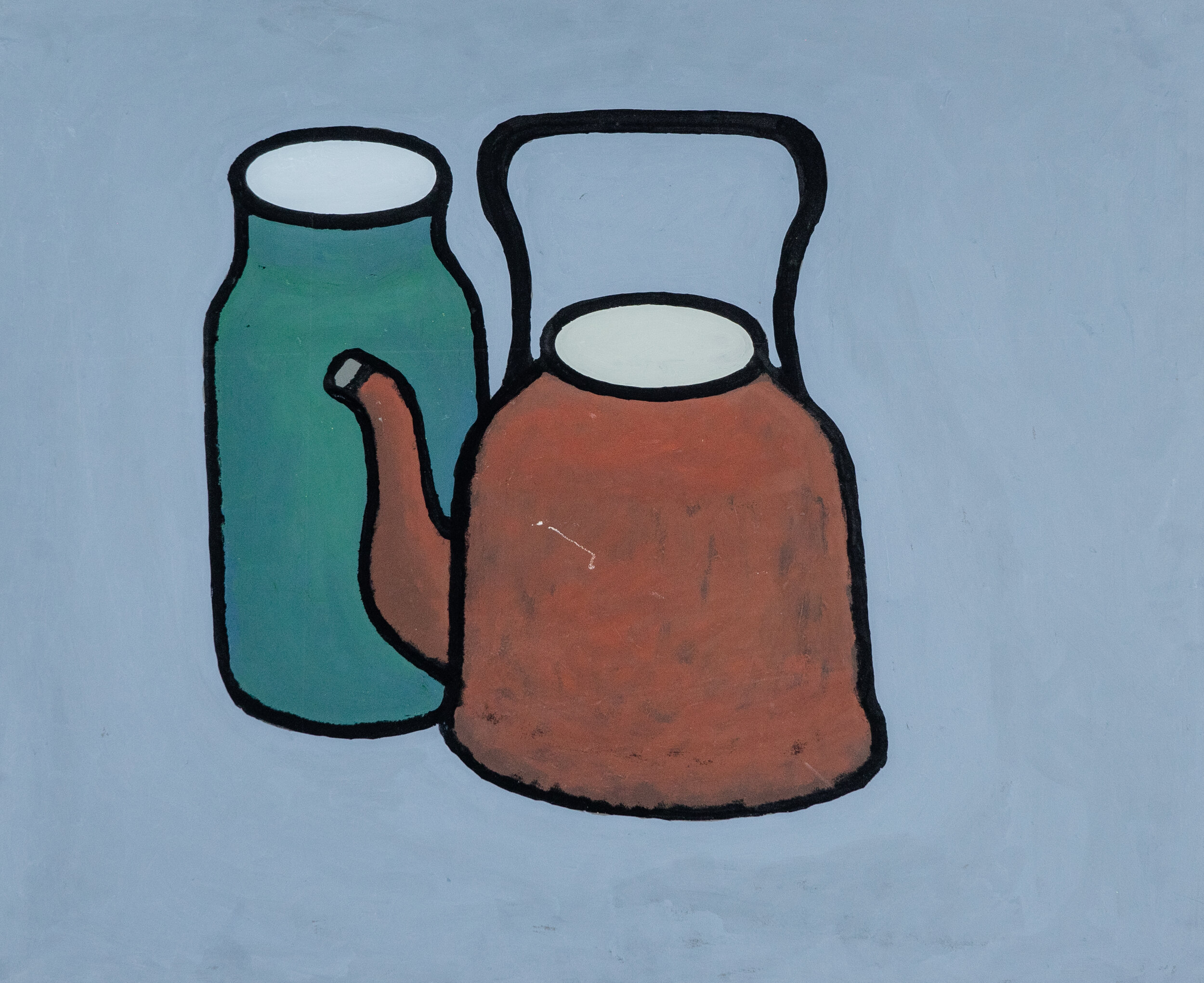

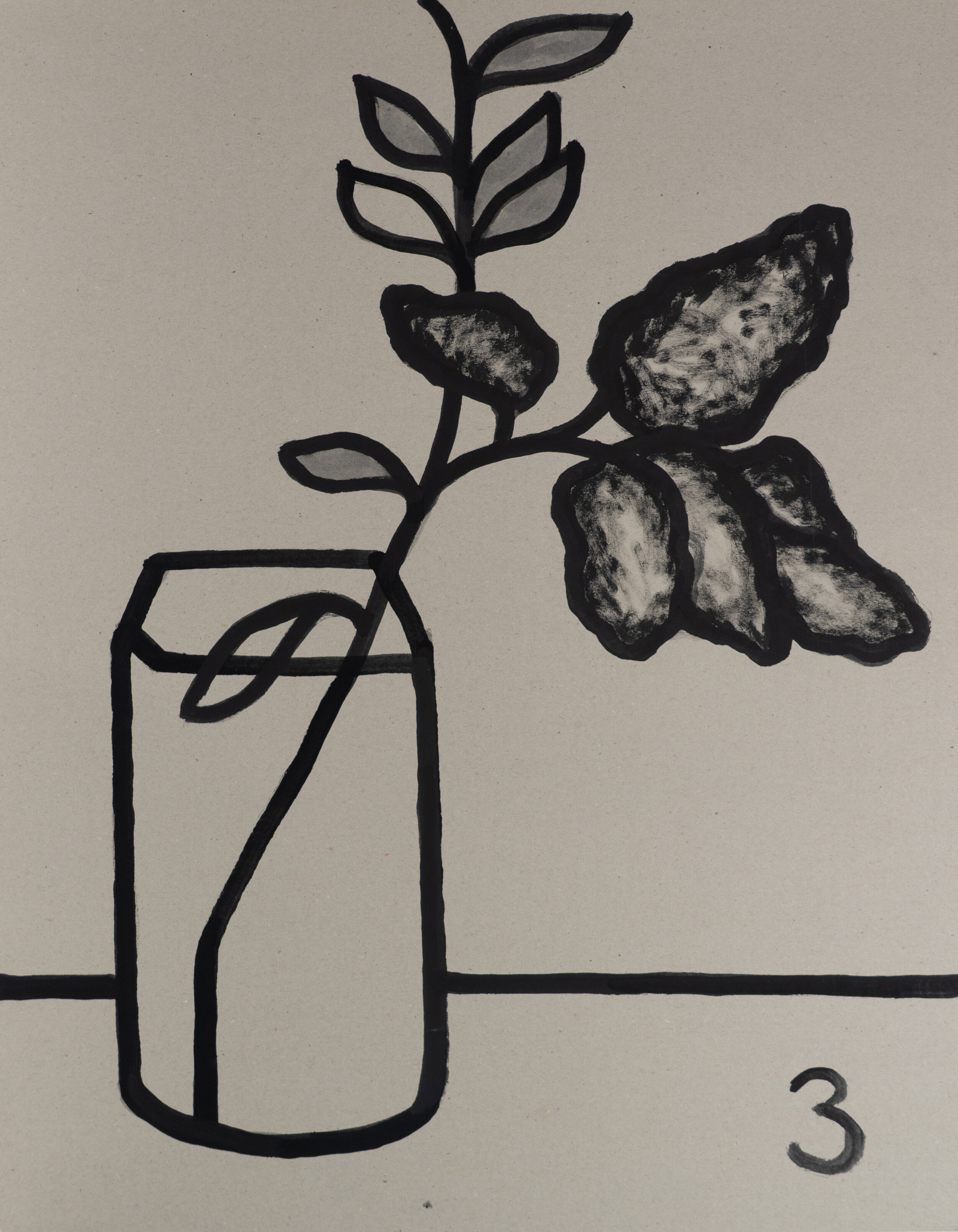

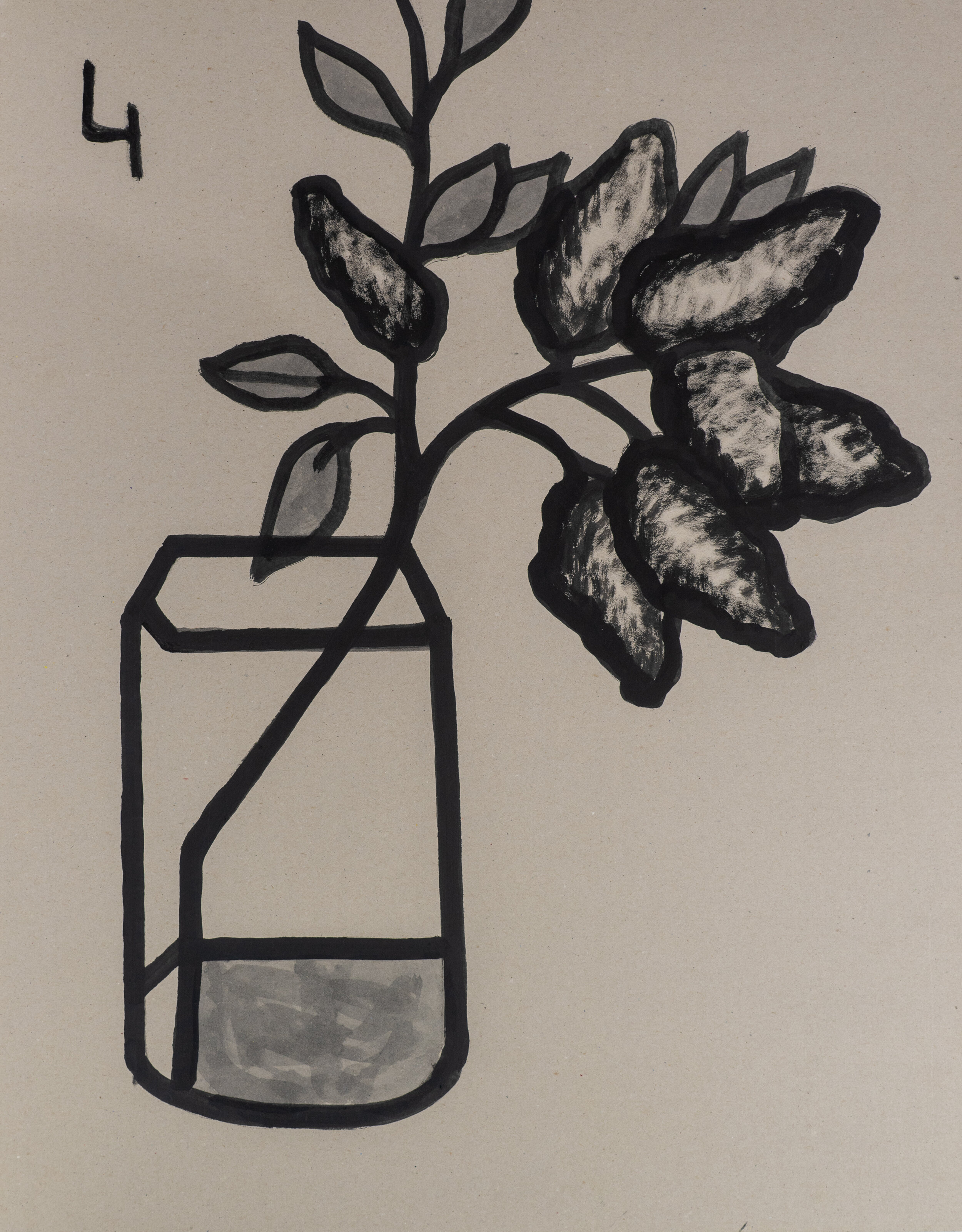

Sapar Contemporary is proud to present new and recent works by the visionary Russian artist Anya Zholud. This will also be the first US solo show by the celebrated Russian artist. Despite suffering from mental illness and depression, Zholud, who lives isolated on the outskirts of Moscow, has produced four significant bodies of work – “Colorful Transgression” (2019), “Period Series” (2019), “Dictionary of Basic Happiness” (2019-2020), and “Dead Ends” (2021). The last three years of the artist’s life were colored by deep loneliness, punctuated by longer hospital confinements, but also highlighted by periods of intense creative output, ambitious institutional exhibitions and biennial participation. The works in the show give us a rare glimpse into the intimate world of Anya Zholud, they represent literally what the artist sees inside and outside her home: barren landscapes, fresh cut flowers, speckled teapots, milk jars, menstrual blood, and empty bottles. Together, they invite the viewer into the threshold – the liminal space – in between clarity and incoherence, happiness and pain, retreat and advancement, form and abstraction that Zholud occupies. In each work, line takes center stage, demarcating objects, emphasizing liminality, and testing the boundaries of reality.

In her native Russia, Anya Zholud is a celebrated artist. She successfully has navigated its male-dominated art scene for several decades, notwithstanding her suffering from debilitating illness and long-term depression. So, what makes Zholud’s work so different, so appealing? Is it her sex? It is her psychosis? Is it her resilience in the face of adversity?

What Zholud sees – barren landscapes, fresh cut flowers, speckled teapots, milk jars, menstrual blood, and empty bottles – is what you get in her work; yet she provides an unique point of view onto the banalities of her everyday life outside the hustle and bustle of Moscow. In an astounding coincidence, she lives in the village of Elektroisolyator – literally “electric isolator” or “insulator,” a material through which current cannot flow freely. Reflecting on this serendipity paralleling her choice of lifestyle, she relays: “It is best to be myself than with random strangers.”

Isolation is not only a fact of life for Zholud but also a means of production. In 2018, long before the global COVID-19 pandemic that sent millions of people worldwide into isolation, Zholud remarked, “I haven’t been outside in two months. Then the curtain was pulled back, and I realized that it’s already a winter.” As a result, she was left with, “Eyes unaccustomed to the daylight; feet that didn’t “remember” how to walk on the ground.”

Her recent series “Colorful Transgression” (2019), “Period Series” (2019), “Dictionary of Basic Happiness” (2019-2020), and “Dead Ends” (2021) attempt to convey this out-of-body experience to viewers. Her aesthetic is characterized by thick black outlines that boldly demarcate their subject matter. Her lines represent thresholds – or liminal spaces – that Zholoud herself occupies as an artist, as a woman, as an individual battling mental illness. While transient, thresholds can be safe and even liberating spaces for the oppressed. Thus, her work functions as a space in between clarity and incoherence, joy and pain, retreat and advancement, form and abstraction.

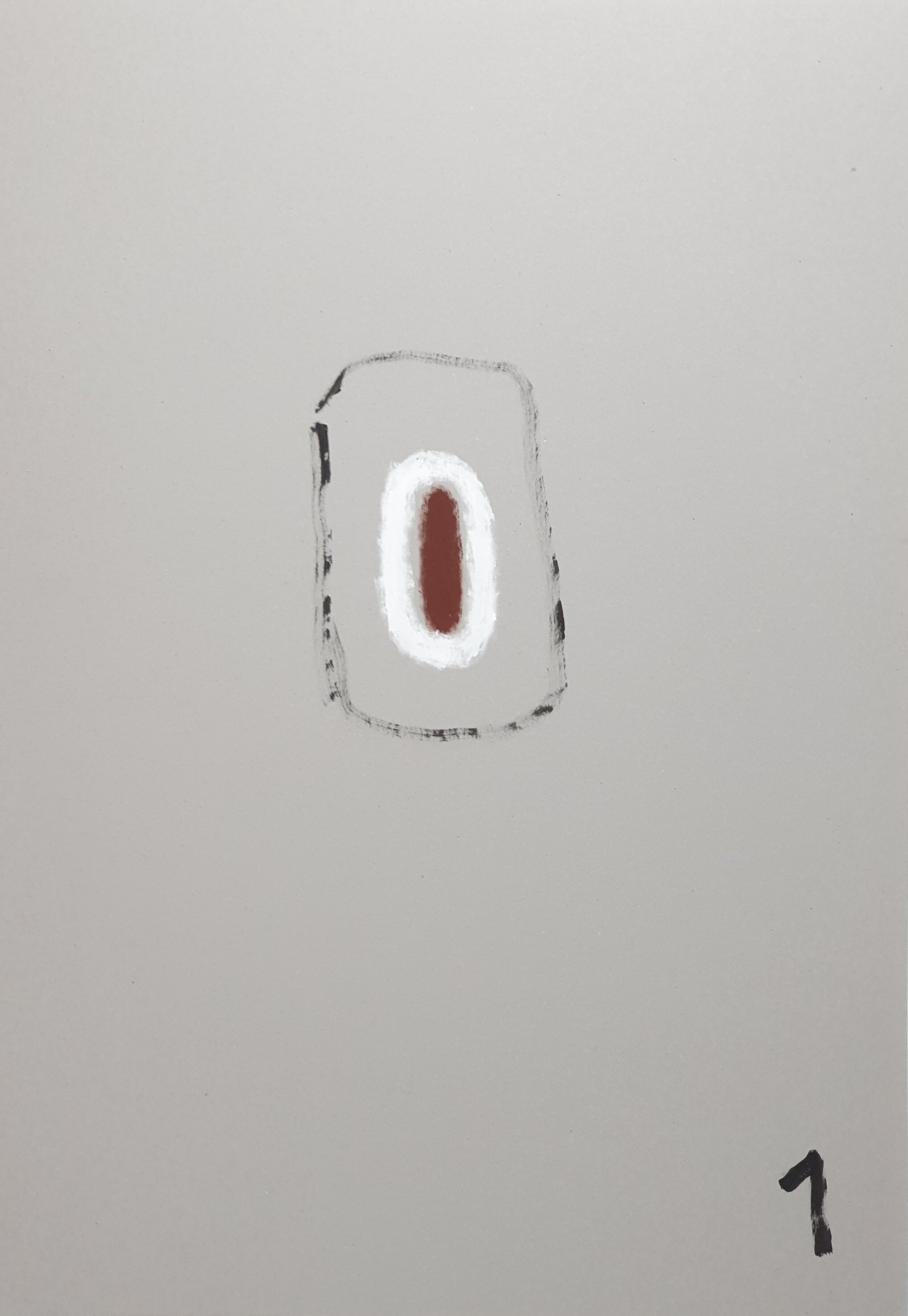

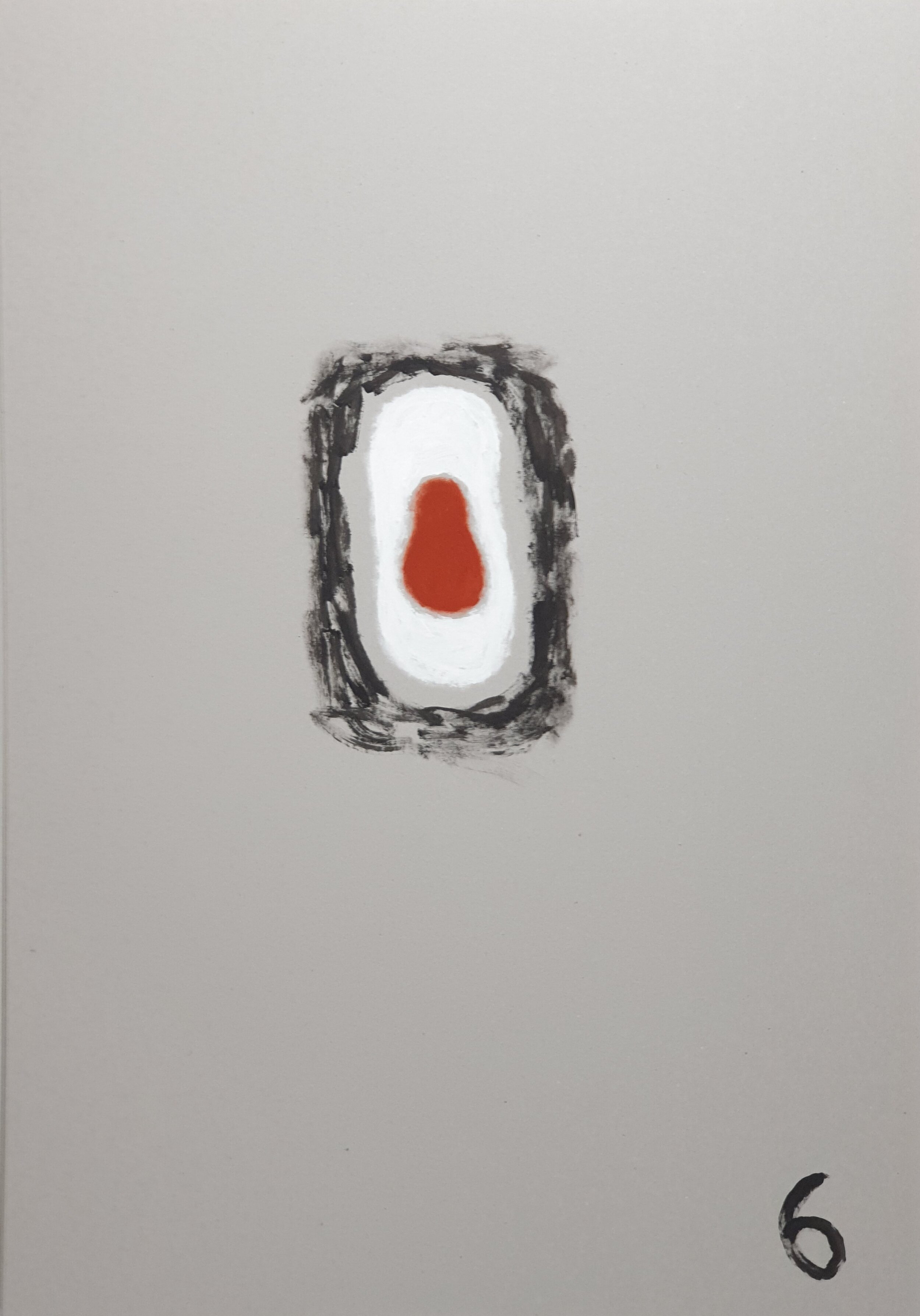

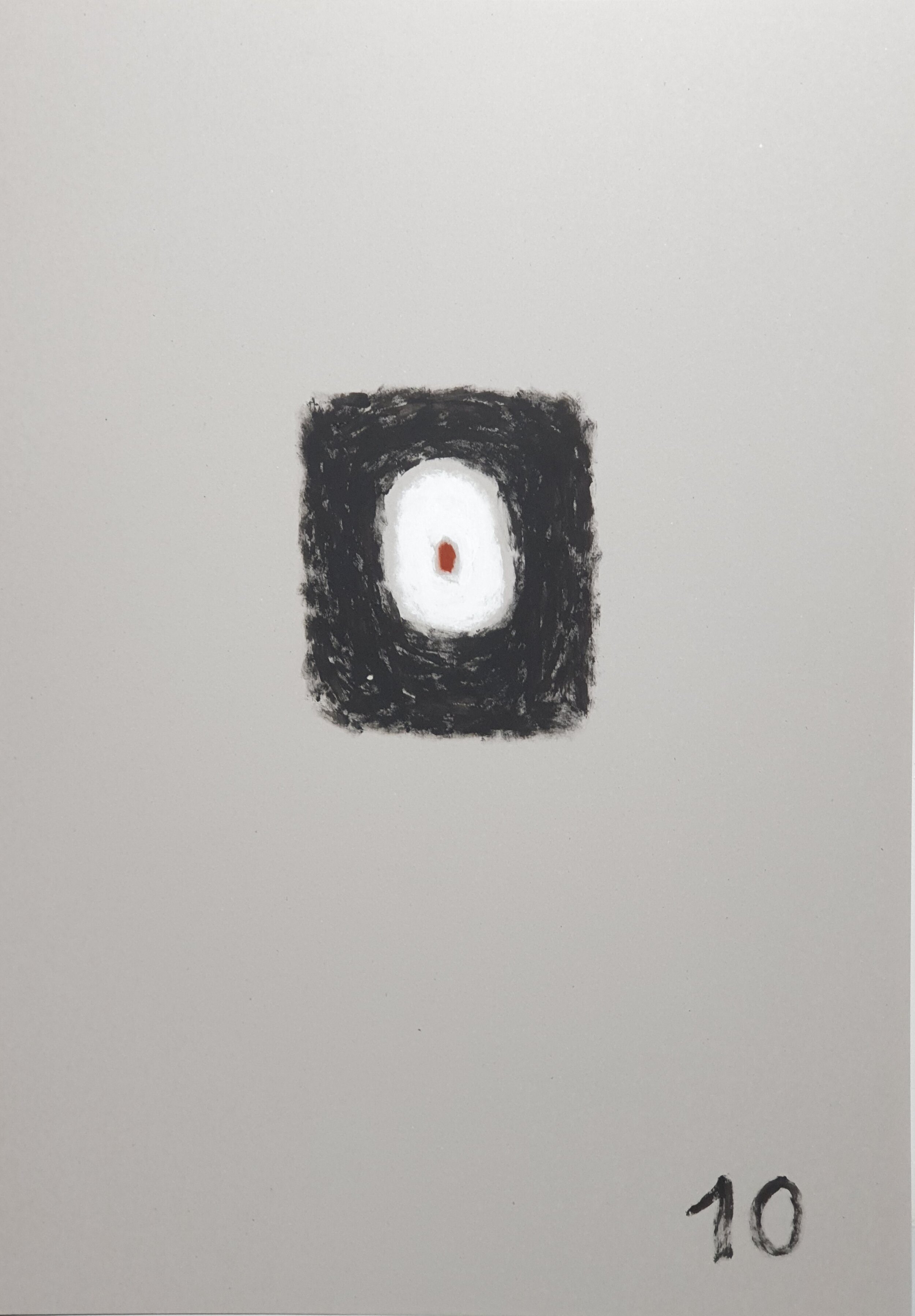

Zholud often speaks in riddles and her language is filled with apparent contradictions. When asked to describe her identity, she claims she is a pravoslavnyy ateist, an “orthodox atheist.” She does not put stock in her sex and gender. “Woman, man, what’s the difference? There are women. There are men.” This egalitarian mindset is admirable; however, her work is not devoid of socially constructed femininity. Zholud self-consciously explores this in “Period Series,” a profoundly vulnerable body of work. While she always invites viewers into the intimacies of her personal life, this series is particularly poignant as it engages her body indirectly through the naturally abstracted form of her menses. What we see is a testament to her body and its ability to function despite its challenges.

-- Dr. Ksenia Nouril, March 2021

About Artist

Anya Zholud is a celebrated Russian artist, who had exhibited in major institutional venues in Russia and abroad. Before she turned 35, Zholud had solo shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, and Garage in Moscow. She took part in in the main Pavilion of the 53d Venice Biennale in 2009, followed by other biennial participations. Zholud graduated from St. Petersburg Art College and the St. Petersburg State Academy of Applied Art and Design. Her work is in the collections of Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Private Contemporary Art Museum in Moscow, National Center for Contemporary Arts, Museum of Nonconformist Art in St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, State Russian Museum, and Tretyakov Gallery. She was nominated for the All-Russia «Innovation» prize in the sphere of contemporary art four times, winning in the “New Generation” category in 2010, and nominated for the prestigious Kandinsky Prize in 2008, 2013, and 2017.

Zholud works in the long tradition of Russian writers and artists who wrestled with the notion of byt, which means extremely basic everyday life, but cannot be translated by a single word in other European languages. Daily life, quotidian existence, material culture, private life, and domestic life: all of these various shades of meaning are present in her work. Zholud attempts to create an outline of the material life around her, making it physically present and also transparent and abstract. Zholud lives in isolation in a rural area outside of Moscow, often struggles with depression and mental illness, but inevitably comes back to her studio where she finds solace. She turns her everyday reality into a bare schematic drawing, and that drawing into a wire installation, or a painting, representing a ghost or a dream of the object. She sometimes refers to her works as “outlines of basic happiness.” Zholud creates over and over again inventories of objects: cups, teapots, milk jars, empty bottle, lamps, shoes, produce, cut flowers — all part of her poetic vocabulary. She re-uses and refines this visual vocabulary endlessly, often working in series of paintings, obsessing over one object for weeks, painting it in multiple combinations and compositions.

Essay

Ksenia Nouril, Ph.D. is the Jensen Bryan Curator at The Print Center, a 106-year-old nonprofit institution in Philadelphia dedicated to expanding the understanding of photography and printmaking as vital contemporary arts. Previously, she held a Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellowship for Central and Eastern European Art at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Dr. Nouril has published two books: Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology (co-editor and contributor, MoMA, 2018) and Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov: Stories About Ourselves (editor and contributor, Rutgers University Press, 2019). She holds a BA in Art History and Slavic Studies from New York University and an MA and PhD in Art History from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.