Faig Ahmed

PIR

November 9, 2021 - January 6, 2022

Opening November 9, 6-8 pm.

Sapar Contemporary announces Faig Ahmed: PIR , the gallery’s second solo exhibition of work by Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed. The exhibition features three large scale new textile works as well as a video work by the artist. The three large carpet works in the exhibitions are titled after poets and spiritual masters whose works had a great influence in the cultural history of Azerbaijan: Shams Tabrizi, Yahya al-Shirvani al-Bakuvi, and Nizami Ganjavi. His title of this exhibition, Pir, encapsulates the multidimensional nature of his work. The ancient Greek word for fire is pyr (πυρ), whereas the word pir in Persian, Turkish, and Arabic means elder or spiritual guide in Sufism, connecting to the three poet-scholars associated with Faig’s artworks. Finally, one of the etymologies of the word Azerbaijan is ‘the Land Protected by Holy Fire,’ as it relates to the ancient Zoroastrian religion established in the region centuries ago.

Artist’s works are conceived with complex layers of historical, literary, mystical, and craft associations. In her essay about the works Fahmida Suleman evokes Rumi’s poem where he likens the entire universe and all that it contains to a carpet created by the divine Carpet-Spreader. Ahmed himself she suggests can be described as a cultural iconoclast who willfully breaks down established forms and boundaries. Ahmed’s works are sites of his own cultural geography, a tapestry of cultural and political history, language, spiritual values, and art. We are fortunate to be co-travelers along his journey.

Pir: Divine Fires and Mystic Guides

Essay by Fahmida Suleman, Ph.D. Curator, Islamic World, Royal Ontario Museum

When the mirror of your heart becomes clear and pure, you will behold images (which are) outside of (the world of) water and earth.

You will behold both the image and the Image-Maker, both the carpet of (spiritual) empire and the Carpet-Spreader.

Jalal al-Din Rumi

Images of weaving, carpets, and textiles abound in medieval Sufi mystical poetry, especially Sufi mystical poetry. The verses by the famed Sufi master Jalal al-Din Rumi (d.1273) identify God as an artist or image-maker and the spiritual realm as a marvelous carpet (farsh), spread open by the all-powerful and all-knowing Carpet-Spreader (farrash). In another verse, Rumi likens the entire universe and all that it contains to a carpet created by the divine Carpet-Spreader. The carpet is a metaphor for creation, bursting with life and full of human stories and emotions, always evolving. Faig Ahmed’s carpets also burst with stories and emotions. He refers to them as ‘cultural geographies’ with distinct histories, personalities, and languages spun within their threads and interwoven in their designs and colours. Faig can be described as a cultural iconoclast. He willfully breaks down and questions long-established and accepted forms and boundaries. During this process, which at times is purposeful and at other times in the realm of his subconscious, he creates powerful and compelling artworks underpinned by his new conceptual framework.

In this series, Faig identifies each of his three works with an important medieval figure connected to his homeland, Azerbaijan. Each figure is a creative disruptor, an innovator, someone who shakes things up, and yet, is a product of his own cultural geography. The earliest is the famous poet-scholar, Abu Muhammad Ilyas ibn Yusuf ibn Zaki Mu’ayyad, known by his pen-name Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209). He was born and lived his entire life in Ganja (hence the nisba or sobriquet ‘Ganjavi’ in his name), in the Arran region of Azerbaijan. Describing himself as ‘a jeweller working with precious gems to create a poetic treasure,’ Nizami managed to retain his independence of belief and artistic expression by refusing positions as an official court poet. His greatest contribution to world literature is his Khamsa (‘Quintet’), five long poems that deal with philosophical themes of human virtue, wisdom, and ethics through timeless stories of love, romance, action, and adventure.

Described as one of the most beautiful cities of Western Asia, Nizami’s Ganja was the capital of Arran region in Transcaucasian Azerbaijan, a flourishing hub of wool and silk manufacture and trade. The southern part of Arran includes the ethnically diverse region of Karabakh (or Karabagh), a centuries-old centre of rug production run by expert female weavers. Faig has designed a Karabakh prayer rug following a Ganja pattern as a tribute to Nizami, using deep reds and contrasting golden yellows with geometric and floral patterns that recall a chahar-bagh or four-part Islamic garden. For Faig, the spirit of this rug represents the people of this region who are equally bold, courageous, and outspoken.

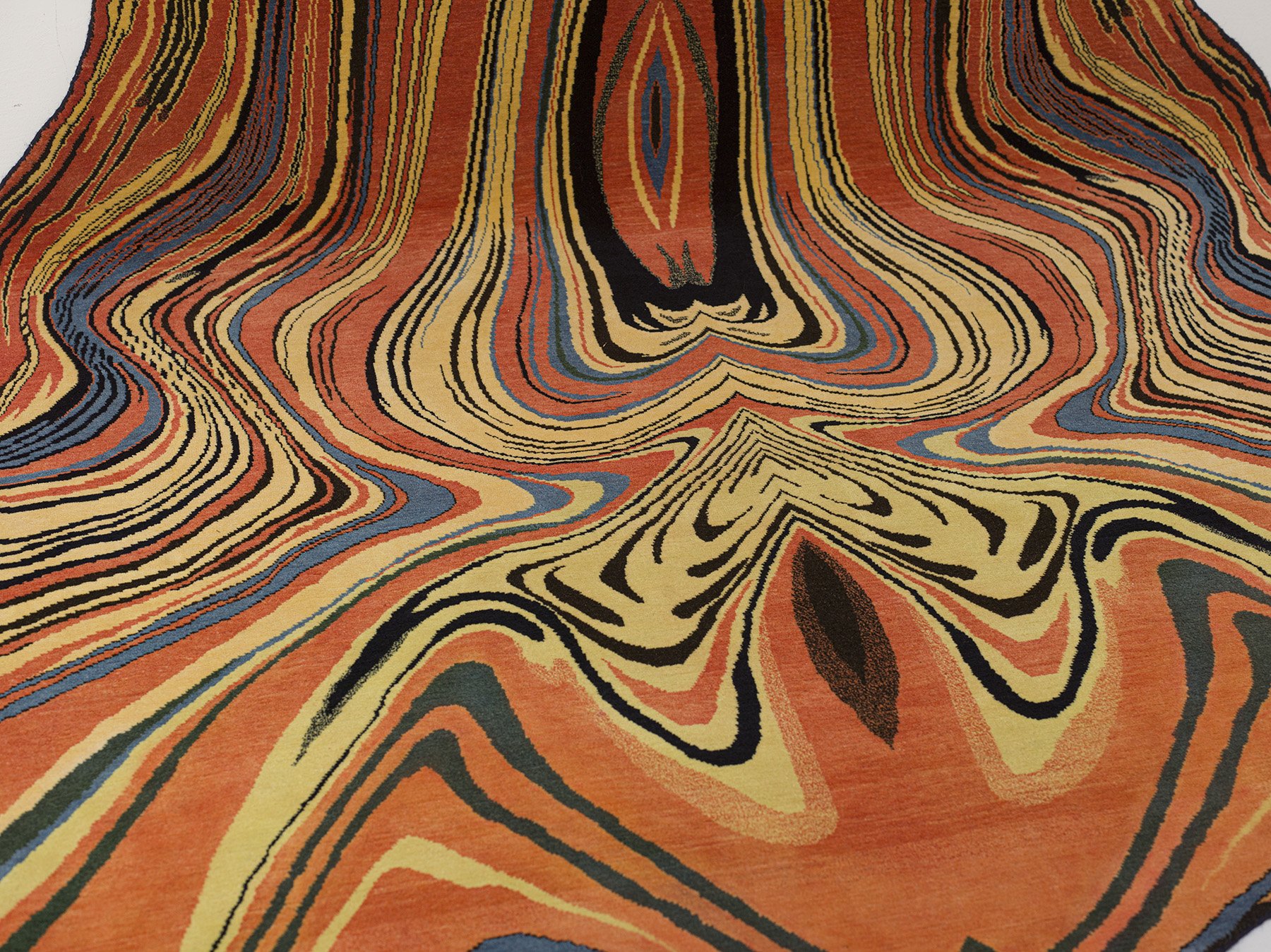

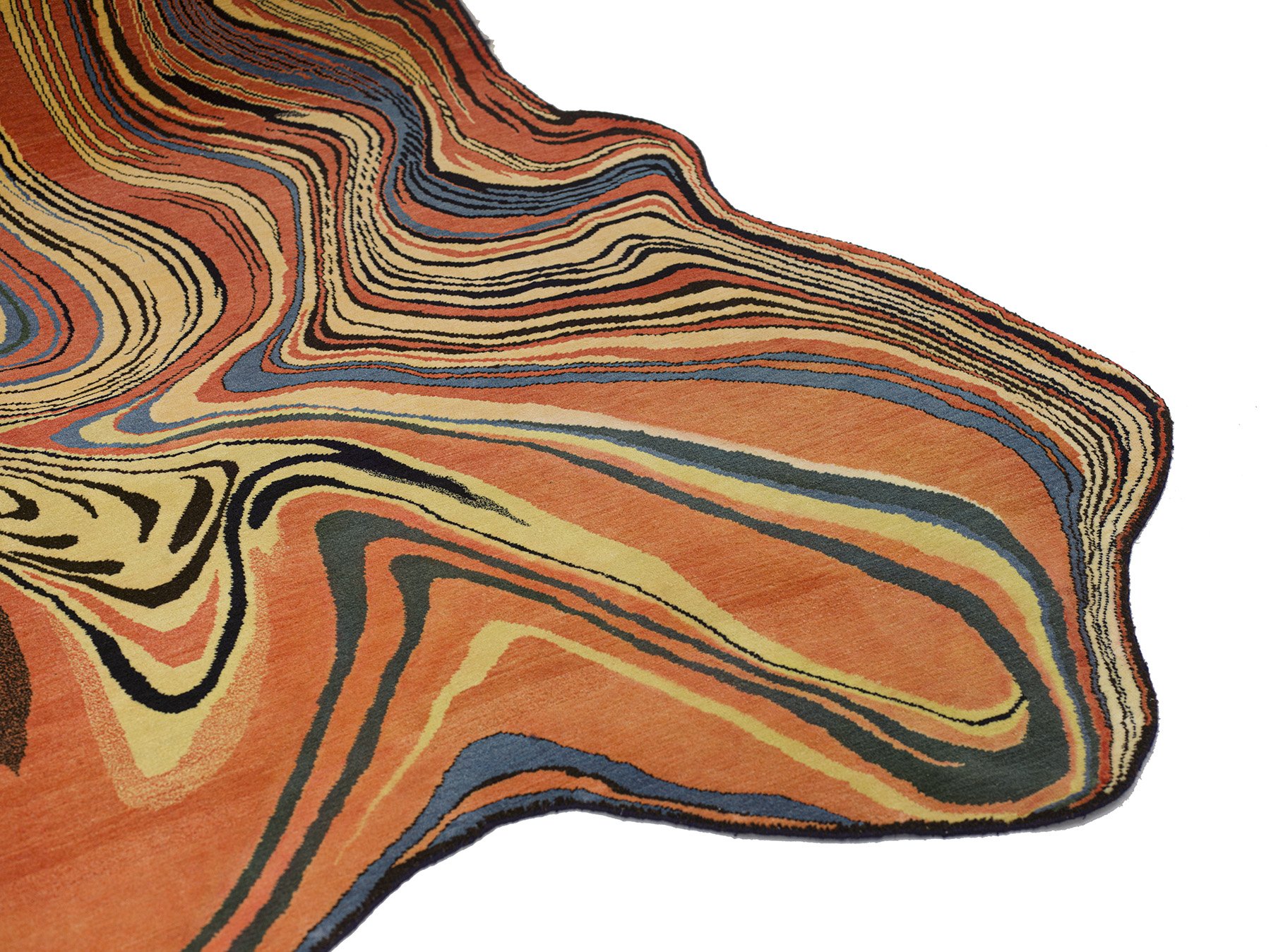

In contrast, Faig’s second work is dedicated to a figure who was a complete outlier of his time and of whom we know very little about – the mystical mentor of Rumi, Shams al-Din Tabrizi (1185–1248). Described as an overpowering person who ‘shocked people by his remarks and harsh words,’ Shams was born in Tabriz, the capital of Iran’s East Azerbaijan Province which was a renowned place of literature, spirituality, and mysticism. The intensity of Rumi’s relationship with this dervish overwhelmed his family and disciples and ultimately led to Shams’ murder. His death was a turning point for Rumi’s spirituality and path of Sufism, inspiring him to compose his book of lyrical poetry, Diwan-i Shams Tabrizi (Poems of Shams Tabrizi). In one poem, Rumi describes God as the Great Weaver:

Weave not, like spiders, nets from grief’s saliva

In which the weft and warp are both decaying.

But give the grief to Him, Who granted it,

And do not talk about it anymore.

When you are silent, His speech is your speech,

When you don’t weave, the weaver will be He.

Here, Rumi likens our lives, full of ups and downs, to carpets which we constantly strive to control as weavers in an effort to dictate our outcomes like the designs and colours on a loom. Rumi advises that we must trust the Great Weaver who has ultimate control and awareness of the patterns of each of our carpets. Rumi’s symbolic use of weaving in this poem may have also been a direct reference to Shams, who was thought to be an itinerant weaver by profession. Tabriz has also been a centre for finely produced carpets for centuries. In contrast to the Karabagh rugs, Tabrizi weavers have a preference for detailed floral patterns often anchored by a central sunburst or multi-lobed medallion (shamsa). Such carpet designs also appeared on courtly book bindings, illuminated manuscripts, ceramic and metal vessels, and architectural tilework. Faig’s Shams Tabrizi carpet surges with organic, swirling floral and vegetal motifs in jewelled tones of silk that gradually dissolve into a black woollen space of nothingness, much like the final stages of a mystic’s spiritual journey: annihilation (fana’) of one’s individual ego within the divine presence, like the flame of a candle in the presence of the sun.

The stage of fana’ resonates in the poetry of Shaykh Yahya al-Shirvani al-Bakuvi (1410–1464), the 15th-century Azerbaijani mystic commemorated in Faig’s final work: ‘Sacrifice both your being and faith; then you will be able to see the beauty of your Beloved.’ Born in Shirvan and buried in Baku, Shaykh Yahya was the second pir or spiritual master of the Khalwatiyya Sufi order which spread across the Ottoman Empire and beyond to Southeast Asia. An important foundation of the order was the practice of khalwat or spiritual retreat combined with voluntary hunger, silence, seclusion, and meditation. Faig’s work in honour of Shaykh Yahya follows a sophisticated and finely-knotted Shirvan carpet design with a symmetrical composition of geometric patterns and a more muted palette than the other works. He describes the characteristics of the people of Shirvan as straightforward and direct but not abrasive, ‘they remain quiet and listen, but tell you what they think in the end.’ This work exudes a meditative and spiritual quality that befits the association with Shaykh Yahya and the Khalwatiyya order.

Faig’s works are conceived with complex layers of historical, literary, mystical, and craft associations. He works closely with his female weavers throughout the process of making as he recognizes and respects the creative power of the women who harness their ancestral knowledge of carpet weaving which has withstood the test of time despite over 70 years of political upheaval and restrictions faced in Azerbaijan during Soviet rule. Through his art, Faig is on a journey of self-reflection and discovery to piece together the many facets of his identity, past and present. Although he did not grow up immersed in Islamic tradition, Sufism or the literary heritage of his forefathers, there were hints of this around him as a child. His great, great grandmother wove her own carpets for her bridal dowry as was customary in her time and his father memorized verses of Nizami by heart. His chosen title of this exhibition, Pir, encapsulates the multidimensional nature of his work. The ancient Greek word for fire is pyr (πυρ), whereas the word pir in Persian, Turkish, and Arabic means elder or spiritual guide in Sufism, connecting to the three poet-scholars associated with Faig’s artworks. Finally, one of the etymologies of the word Azerbaijan is ‘the Land Protected by Holy Fire,’ or simply, ‘the Land of the Fire’ as it relates to the ancient Zoroastrian religion established in the region centuries ago, of which traces still remain with the presence of fire temples in different parts of the country. Faig’s works are truly sites of his own cultural geography, a tapestry of cultural and political history, language, spiritual values, and art. We are fortunate to be co-travellers along his journey.

Faig Ahmed (Sumqayit, 1982) lives and works in Baku, Azerbaijan and graduated from the sculpture department of Azerbaijan State Academy of Fine Art in 2004. He represented Azerbaijan at the nation’s inaugural pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and participated was a part of the Azerbaijan pavilion in 2013. He is well known for his conceptual works that transform traditional patterns and the visual language of carpets into contemporary sculptural works of art. Ahmed is among a new wave of contemporary artists reimagining textile traditions and histories of pattern making to produce conceptual works that break away from conventions . His art brings the ancient textile traditions into a global contemporary art context. Ahmed explores fresh new visual forms that challenge our perception of traditions and iconic cultural objects. Ahmed’s artworks engage the viewers through its unexpected marriage of traditional crafts with hyper-contemporary, digitally distorted images often in the form of pixilation, three-dimensional shapes and melting paint that alters the pattern on the rugs. The artist’s avenues of artistic inquiry are connected to patterns, language, calligraphy and how those are reflective of mystical practices, ancient scriptures, regional histories. In addition to textile Ahmed’s works in broad range of mediums including video, performance, drawing and installation.

Ahmed was a subject of a solo show at Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma . His upcoming survey exhibition will open at San Luis Obispo Museum of Art in 2022. Other museum exhibitions in 2022 include The Dowse Art Museum, New Zealand and Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University.

Ahmed’s works can be seen in public collections globally, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum, Palm Springs Art Museum, Seattle Art Museum, RISD Museum of Art, Chrysler Museum of Art, George Washington University, Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN; Currier Museum of Art, NH; Bargoin Museum, France; MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art, Krakow, Poland; The National Gallery of Victoria, Australia; Arsenal art Contemporain Montréal, Canada; The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Norway, Istanbul Modern. His work is also found in private collections such as the West Collection, Philadelphia; the Microsoft Art Collection, Wake Forest University, the collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody, New York; Galila’ Collection, Brussels; Ranza collection, Rome; Jameel Foundation, Espacio SOLO, Puerta de Alcalá, Madrid; London and H.H. Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, UAE.