Lifted: New works by Marela Zacarías (Mexico/US)

Curated by Barbara Stehle, Ph.D.

December 8, 2020 – January 11, 2021

Opening events December 8 and 9, 6-8 pm (we are welcoming groups under 8 people)

Sapar Contemporary is delighted to present new works by Marela Zacarías and the artist’s second solo show with the gallery. The exhibition, titled “Lifted,” is also the grand finale of this trying and tumultuous year, a crescendo that is colorful, uplifting, and nuanced.

Zacarias has spent much of her time in 2019 and 2020 on the West Coast. She was working intensely on the commission of five sculptures spanning 250 feet for the Seattle Tacoma International Airport. These monumental colorful sculptures were inspired by the culture and palette of the Pacific Northwest. The works refer to the bodies of water around Seattle, their undulating forms evoking expansion and movement. It took two and a half years with a dedicated studio team to complete the project. It will soon be on view.

While in Seattle, Zacarías also returned to her early mural painting practice for MadArt. The exhibition room presents an installation of vibrant floor to ceiling paintings surrounding a pyramidal structure with a sculpture at its center. The iconography and the structure of the installation give homage to the esthetics of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent in Xochicalco, Mexico, one of Zacarías’ art historical inspirations.

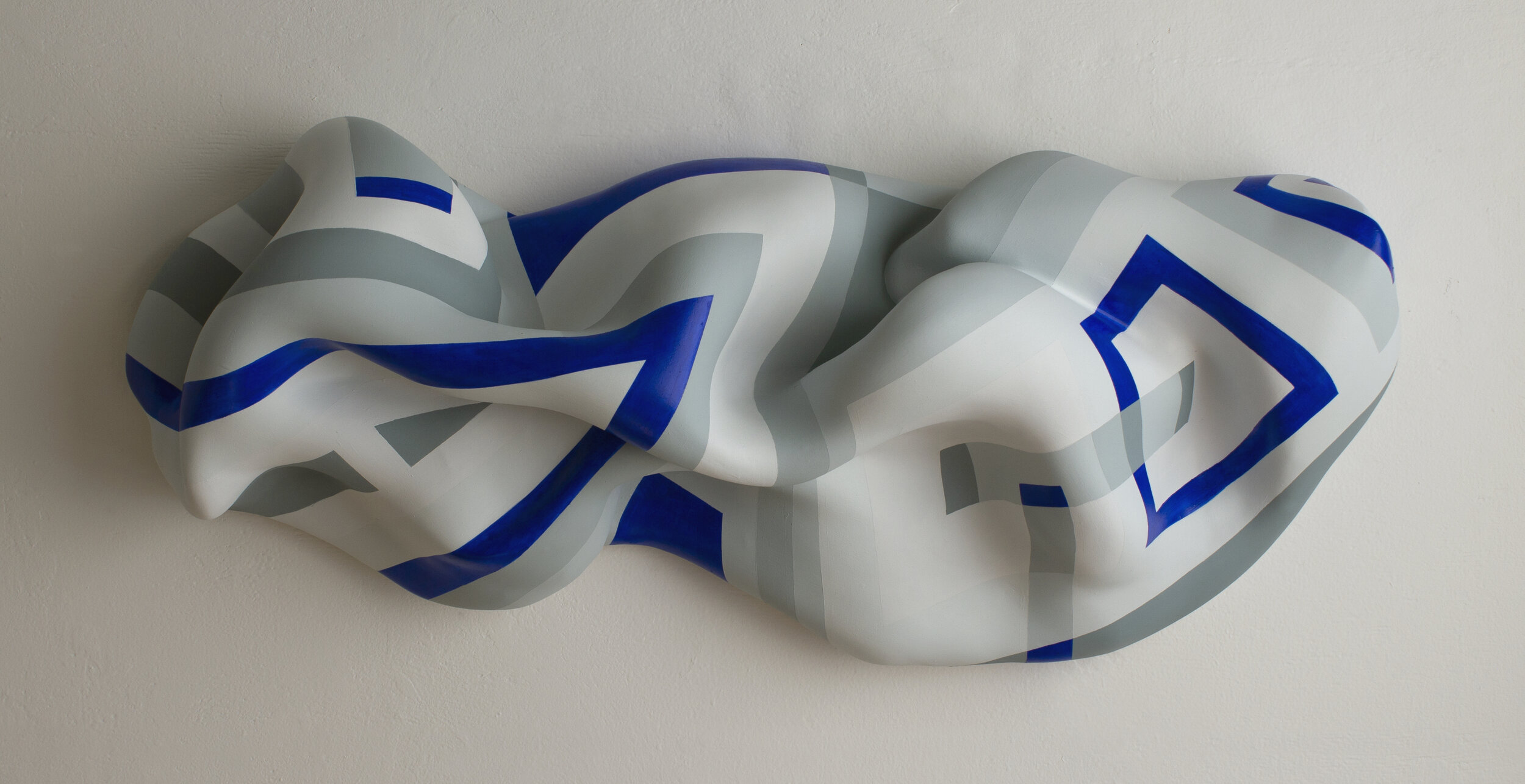

After the physical demands of these epic projects, Zacarías returned to her New York studio for a period of solitude. Replenishing and reflecting in the quietness of an isolated space, she continued to create. Her new painted sculptures are of a smaller size, personal and luminous. Their volumetric forms hang on the walls. They have the energy of a Haiku: condensed and lively. Their whole physicality speaks of a privileged time, one of making space and finding pleasure in the intimacy of creation at a human scale.

What comes through very clearly in the new works is Zacarías' continuous engagement with the history of abstraction, from the American continent to European modernism. Her references are playful rather than self-conscious. They shift with ease from Russian Constructivism to Mexican pigments; biomorphic curves dialog with the artist's personal version of American Neo-plasticism. Clearly, Zacarías’s works have in them the rigor of a practice, both physical and intellectual, yet their presence is everything but serious and academic. They move through space freely, freshly and unconventionally.

A few thoughts about Marela Zacarías’s wall sculptures after a long passionate conversation with the artist.

By Barbara Stehle

One of the major narratives of modern art is the adventure of the painting off the wall. Painterly works made it to the floor and outdoor environments, leaving the canvas and other conventions behind. The counterpart to this story is the migration of the sculpture from the ground to the wall, from outdoors to indoors. Liberated by the avant-gardes of the twentieth century, works of art found new ways of interacting with space. Marela Zacarías is further developing this history. In her work painting is catching back up to the sculpture on the wall, espousing its form and becoming its skin.

Zacarías’ practice evolved naturally from painting murals to creating sculptures to take their place. With time, the works found their full freedom of movement, exploring architecture even further: hanging from the ceiling, wrapping around other objects, sitting on the floor... But the artist has always expressed a continued commitment to exploring the possibilities of wall works, creating an intimate dialogue with the architectural site.

In the Renaissance, the Florentine Della Robbia family made polychromatic bas-reliefs, often in roundels but not always, that were commissioned for architectural settings. You find them in Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel perched in pendentives and positioned under cornices. Their colorful designs brighten the walls in place of frescoes or stained glass. The Della Robbia family worked in ceramics: white, blue, greens and reds make up most of their palette. The works were made out of a secret formula invented by the family. They have not aged a bit. Marela Zacarías inscribes herself in this tradition, moving sculptural paintings to the age of abstraction. Her works are not in ceramics, even though the appearance of their fresh and smooth surface leads many to think so, instead they are made of many materials rather than one. Neither cast nor chiseled she had to invent her own formula to create them. Zacarías developed her particular technique through trial and error. She tested several mixtures and structures before ending up with a wooden construct under rolls of window mesh. They form the skeleton of the work which is then covered by many layers of a compound mix, and finally Polymer. It takes several months to create each object before it is ready to paint.

I did not expect the construction materials to be what they are. Certainly I would not have thought of window mesh. When the artist told me, I was surprised. But then I also did not expect Degas to use several paint brushes and a metallic armature for his Little Dancer before covering the whole thing with clay and beeswax. Degas even used wine cork bottles, a tambourine and old floor planks for some of his sculptures. At times, Zacarías too has used found materials in her works. Artists in general, but sculptors especially, often look outside of the art shop to solve their structural issues. The things that radiographs reveal will make you completely rethink what it is to be a sculptor.

Marela Zacarías takes part in a history that follows up Degas’s radical break with traditional sculpture. The artist is not interested in the multiple editions usually associated with sculptural fabrication. Rather she is exploring the possibilities of the medium one piece at a time. Degas himself never actually cast his sculptures nor wanted to do so. It was done posthumously to save the work from disintegration as the wax was crumbling. All he wanted was to experiment in three dimensions in a way that related to his painterly work. Degas’s work opened the way to the inventions of modern sculpture practices. And like Zacarías, Degas was fascinated by motion, something sculpture is often thought to be less capable of expressing.

Zacarías’ work often records in an abstract three-dimensional form the impulse of a movement. To me, the work connects the sensual animation of Bernini’s drapery to the structural abstraction of Frank Gehry. The window mesh Zacarías uses to construct her pieces comes from the architectural world and is sturdy, yet it offers a surface akin to weaved fabric, albeit in metal. Like many fabrics, the thin mesh easily takes to embodying motion (think of the dancer Loie Fuller creating volume with her silken costume through her movement). Because of its metallic nature the material creates folds and waves. One move after another it morphs and the sculpture finds its form.

As it turns out, Zacarías loves to dance. Her ease with space and gesture leaves a physical trace in her work. Zacarías’s creative process is even a dance of sorts. The artist’s body moves around the wooden structure, with the mesh, articulating it in a diversity of ways: gathering, stretching, folding, pinching etc… Years of experience come into play in this physical dialogue. The mesh reacts to the artist’s moves and vice versa. Everything takes place intuitively in this creative dance. If the momentum is lost it compromises the piece’s flow, and the sculpture has to be started over from scratch.

It is the spirit of the original flow that the artist looks to preserve in the next stages of creation, so that each finished piece conveys the dynamism of its genesis. Some of the small works are the result of few gestures. Some, despite their small scale, present an unsuspected density and complexity. Large or small, Zacarías’s work exudes liveliness and expression. The logic of a fabric in movement remains palpable in the pieces. That is why for many people, textiles come to mind when looking at her work; a comparison reinforced by the works' smooth and colorful surfaces. For some the skin of the sculptures evokes satin weave silk, for others the quality of ceramic.

Zacarías is a craft lover, she admires both ceramics and textiles. Born in Mexico to an anthropologist mother who took her on trips, she has a deep love and respect for indigenous artworks. Zacarías has seen many beautiful examples of indigenous work since childhood and continues to look for more. As a painter, she finds in these works a palette of colors and compositions that stimulate her creativity. She knows the history of pre-colonial Mexican art very well and has found in it numerous sources of inspiration. Understanding history is something that is crucial to the artist. She has a passionate interest in the global development of abstraction. Zacarías combines her artistic practice with a scholarly activity, one informing the other. Each creative project comes along with an in depth research process. The site and context of the works set the parameters of Zacarías’s reflection. She takes into consideration culture and nature, social and historical facts. The spirit and stylistic elements of the new work will reflect this investigation.

One of Zacarías scholarly expertise is on the American Abstraction Artist group (AAA) and on their activity during the great depression and after. Her teacher and mentor, the lyrical abstractionist Emily Mason, was the daughter of Alice Trumbull Mason, one of the AAA women artists. Zacarías speaks of these two women with warmth and reverence. She knows their body of work inside out and has devoted much time to her relationship to Trumbull Mason, a geometric painter. Zacarías can quote many artists who were relevant to her in the history of American modernism, from European emigrants like the Mondrian to WPA painters. Being a woman abstractionist, Zacarías is profoundly moved by stories of women contributing to the vocabulary of abstraction. In fact, she is quite unstoppable on the topic and pulls books and photos to point to things that matter to her. The diversity of her references is impressive. Names like Sonia Delaunay and Anni Albers come along, but the artist also refers to the contribution of anonymous women. She has a fondness for abstract practitioners who work in fields not sufficiently quoted in academic history of abstraction.

Zacarías considers the Ndebele women painters from South Africa who decorate the façades of their homes with colorful geometrical patterns as examples of great abstraction. She admires the quality and designs of Middle Eastern textiles and referred to them in a series of works, reconnecting this with part of her own ancestry. More recently the artist has been focused on studying the work of Mayan Chiapas weavers. Their bright geometrical designs echo some of the abstract features of Mayan pyramids. The artist is inspired by these anonymous women who used their creative practice as an act of resistance against colonizers. They preserved their cultural heritage by passing their knowledge down to their daughters.

Like many non-white abstractionists, Marela Zacarías does not see abstraction as something disengaged from political and social history. She comes from a muralist tradition of social expression. She admires Diego Rivera for making space for Mexican culture in modernism. The social consciousness attached to Bauhaus pioneers of abstraction is something the artist understands well. It is something she found in the AAA group too: Abstraction as something that can provide an esthetical and psychological comfort to people without privilege. Zacarías abandoned figuration when she felt abstraction could provide more artistic freedom, but she never intended to give up social narratives.

Russian constructivism and Mexican muralist movement have an interconnected history, even though one is representational and the other completely abstract. These two artistic languages are not necessarily at odds when it comes to defending ideals. In one of Zacarías murals painted in 2020, I recognized an element of El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. The artist noticed the reference too: the Red Army beating the Tzarists. It clearly had popped up without her planning it. I mentioned the fact that to me El Lissitzky was the first to have made political abstraction work. She agreed and laughed. She loves his geometrical sculptural paintings, the Prouns.

There is so much more that we spoke about, too much for one article. I will just conclude with this final thought: Marela Zacarías painterly vocabulary is the territory of unexpected encounters and intersections. Through their colorful elegant presence Zacarías works are a generous opening to others and their history.

About Artist

Marela Zacarias works with a labor-intensive process that merges sculpture with painting. She fabricates forms out of wire screening attached to wooden supports or found objects to which she applies layers of plaster to create undulating forms. Through sanding, polishing, and painting, she creates sculptures with the quality of fabric, filled with movement and expressive quality. She then paints the sculptures with original patterns and geometric abstract shapes that are inspired by her research. Her work is characterized by an interest in site specificity, socially committed history and current events. Zacarias has had solo exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum; Praxis Gallery, the National Arts Club and at Art at Viacom at 1515 Broadway building all in NY; and at the Brattleboro Museum, Vermont. She has taken part in group exhibitions at the British Society of American Art, Praxis Gallery, Y Gallery, Rush Arts Gallery and El Museo del Barrio, all in NY. Zacarias has received large-scale permanent site-specific commissions from The Sea-Tac International Airport, Seattle; Facebook HQ, CA; The William Vale in Williamsburg, Brooklyn; the American Consulate in Monterrey, Mexico. Her murals can be found in Washington DC, Virginia, Connecticut, Ohio, Mexico and Guatemala. Zacarias has had residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, Johnson; University of Connecticut; Storrs; and at the Corcoran School of Art, Washington, DC, among others. She was profiled in the Art 21 New York Close Up Series in 2013, 2014 and 2016. Zacarias received her BA from Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, and her M.F.A. from Hunter College, New York. She lives between Brooklyn, NY and Mexico City.

About Curator

Barbara Stehle, Ph.D. is an art historian and independent curator. She worked at the Pompidou Center in Paris before moving to the US. She currently teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design and directs Art Intelligentsia through which she offers art historical services. She has given a Tedx talk about “Architecture as Human Narrative” and writes mostly about European Art, Architecture and Women’s contribution to the art historical field. She recently completed an essay for African American Abstractionist Lula Blocton upcoming monograph