Mahi Binebine: ON THE LINE

Essay by Rachel Winter, Assistant Curator, Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University

February 21, 2024 - April 5, 2024

Opening February 21, 5-8 pm

Conversation with Curator Rachel Winter: Friday, February 23, 6-8pm

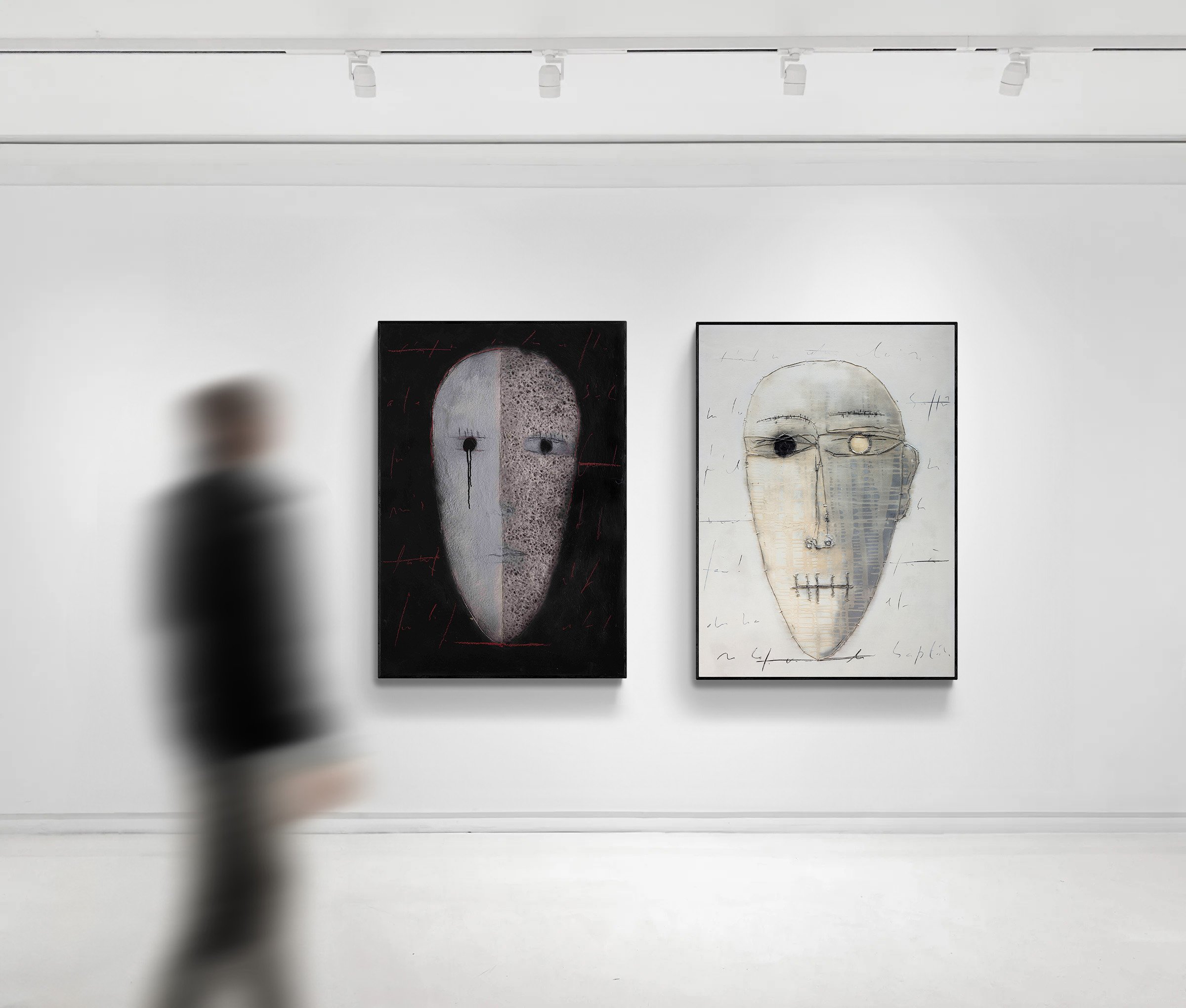

Sapar Contemporary is proud to present the first solo exhibition of an important Moroccan artist Mahi Binebine in more than two decades. Binebine is a cultural figure in Morocco, equally well-known for his contribution to the literature and the visual arts. New York City was his creative home in 1990s. The artist is returning to New York with the paintings and sculptures from the recent decade and a selection of recent works on paper. Binebine's artworks trace the contours of individuality, family, history, and sociopolitical change in North Africa in ways that are once universal and particular, using the line to illustrate scenes suggesting that at any moment, we could also be subjects of this narrative.

MAHI BINEBINE VIEWING ROOM

I see the contours touch then soon overlap. - Michel Butor

I. Drawing Family

In his novel Les funerailles du lait (Mamaya’s Last Journey, 1994), Moroccan writer and artist Mahi Binebine recounts a defining period in his family’s history. Born in Morocco in 1959, Binebine was one of seven children. Raised by his mother, his father—a man known for close ties with Moroccan royalty, including King Hassan II (1961–99)—abandoned them. During Binebine’s childhood and teenage years, many of Morocco’s young adults spoke out against Hassan II’s authoritarian policies. In 1971, Binebine’s older brother Aziz took part in a military coup that failed to overthrow the king. Aziz was then disappeared, spending 18 years imprisoned in the Tazmamart desert camp with 55 others; Aziz was one of few who survived, and was later released (2).

During moments of this protracted family tragedy, Binebine was in Paris studying mathematics, which he later taught. He published his first book in 1992, and then emigrated to New York from 1994–99 before returning to Morocco in 2002 where he has lived since. Following Binebine’s successful career as a writer, he became an artist working across painting, drawing, and sculpture to fabricate reflections on Moroccan history and lived experiences under different political regimes. His writing and his painting are, and always have been intertwined; he is now one of Morocco’s most well-known and important artists.

This familial experience bound to loss, love, and political turmoil is formative to Binebine’s artistic practice. His poetic and emotional retelling of family viscerally yet poignantly illuminates what many endured under Hassan II’s government and in subsequent decades. Morocco’s history of censorship, imprisonment, and brutality becomes entangled with contradictory moments of tenderness and terror that prompt deeper thinking about the fabric of family when its structure is threatened from within and beyond. Binebine’s portraits trace the contours of individuality, family, history, and sociopolitical change in ways that are once universal and particular, using intricate lines to illustrate scenes suggesting that at any moment, we could also be the subjects of this narrative.

II. Drawing is a Process

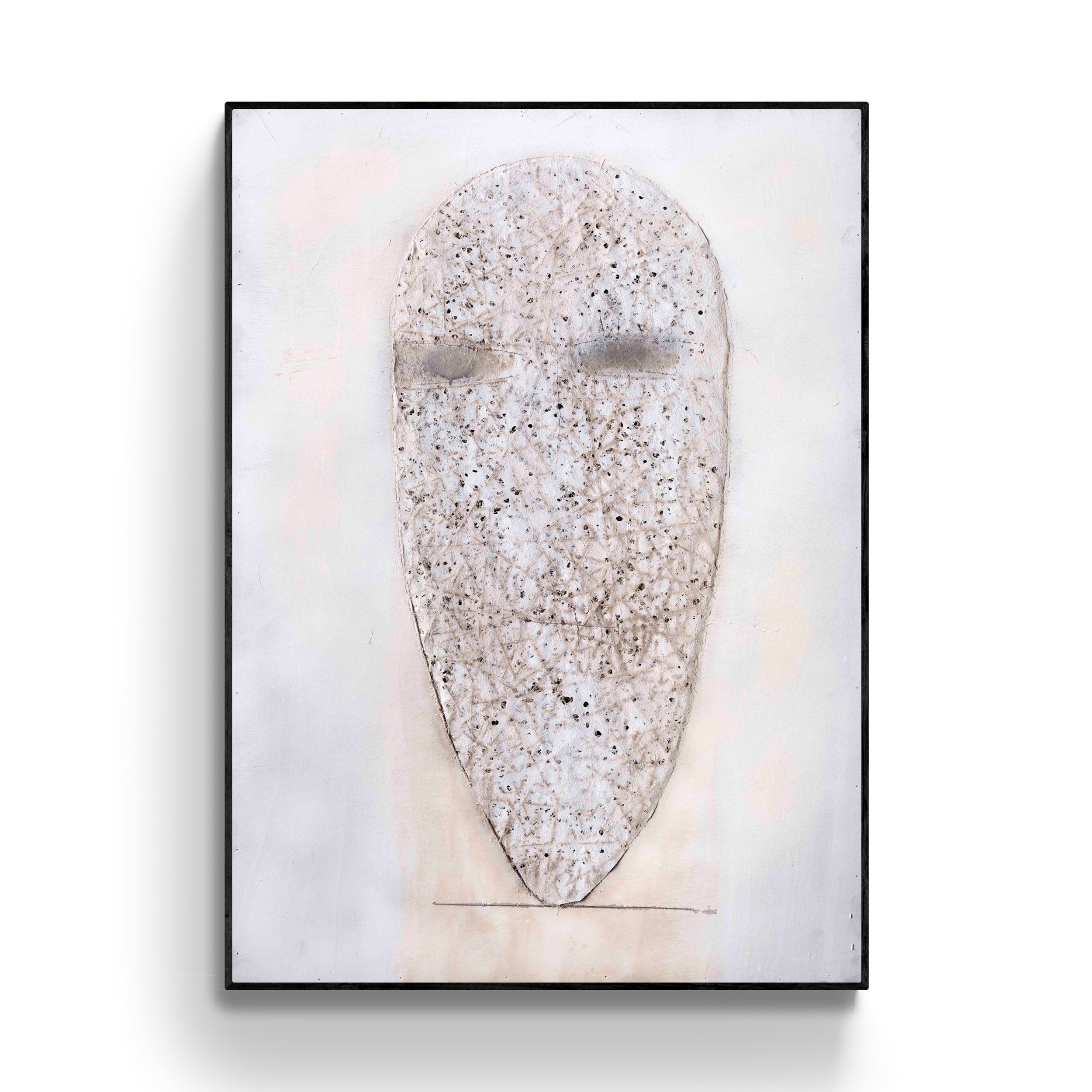

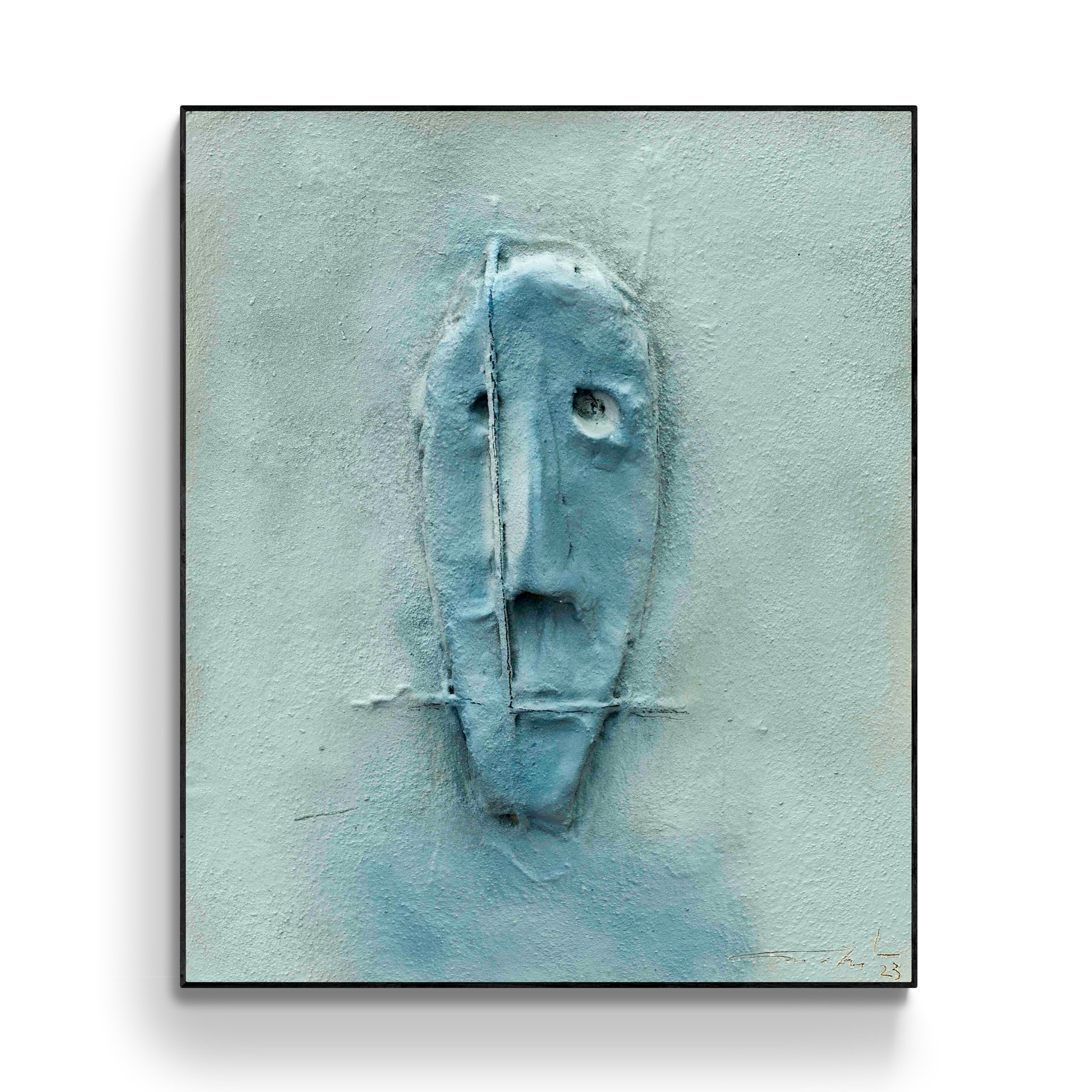

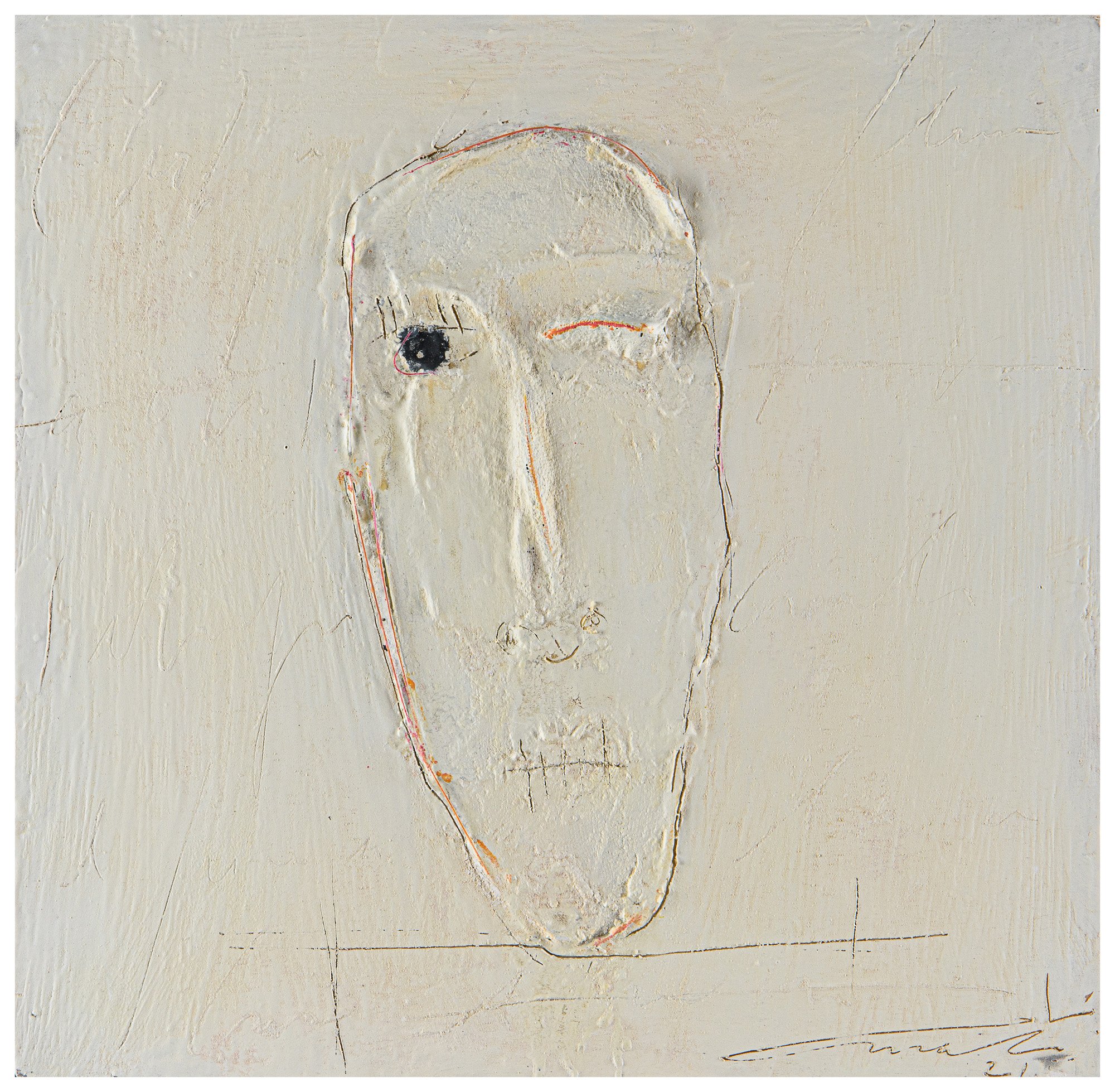

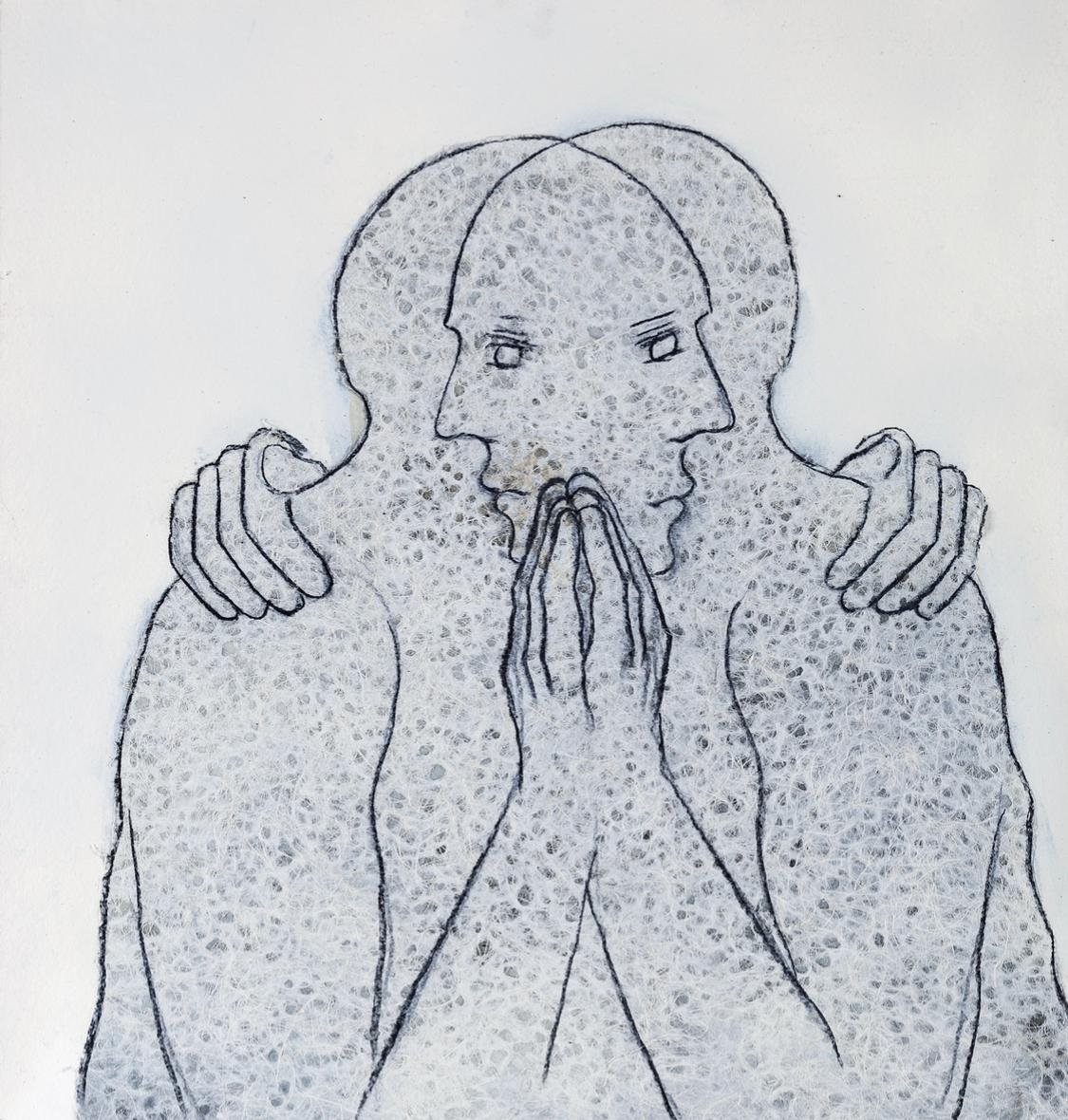

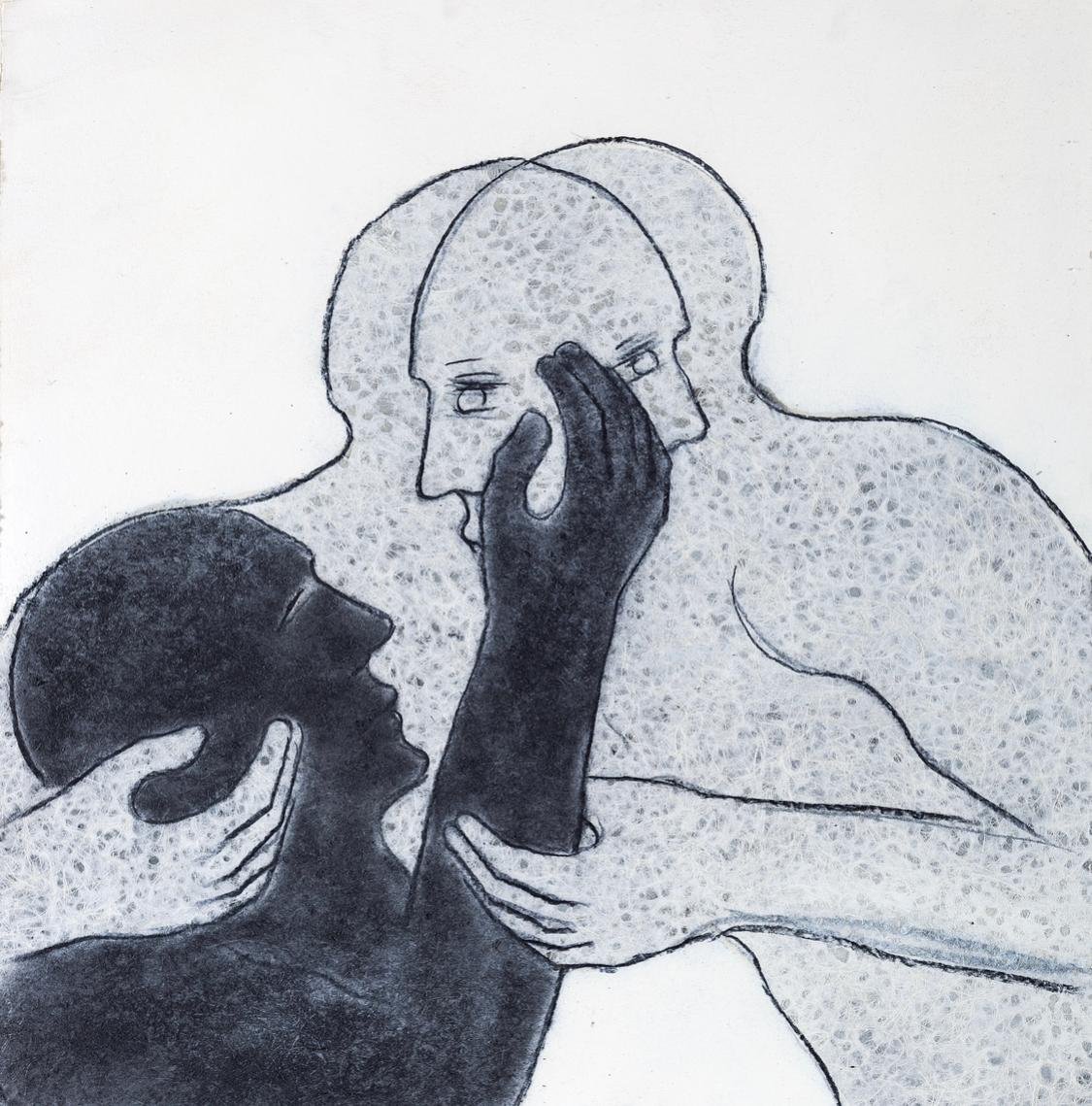

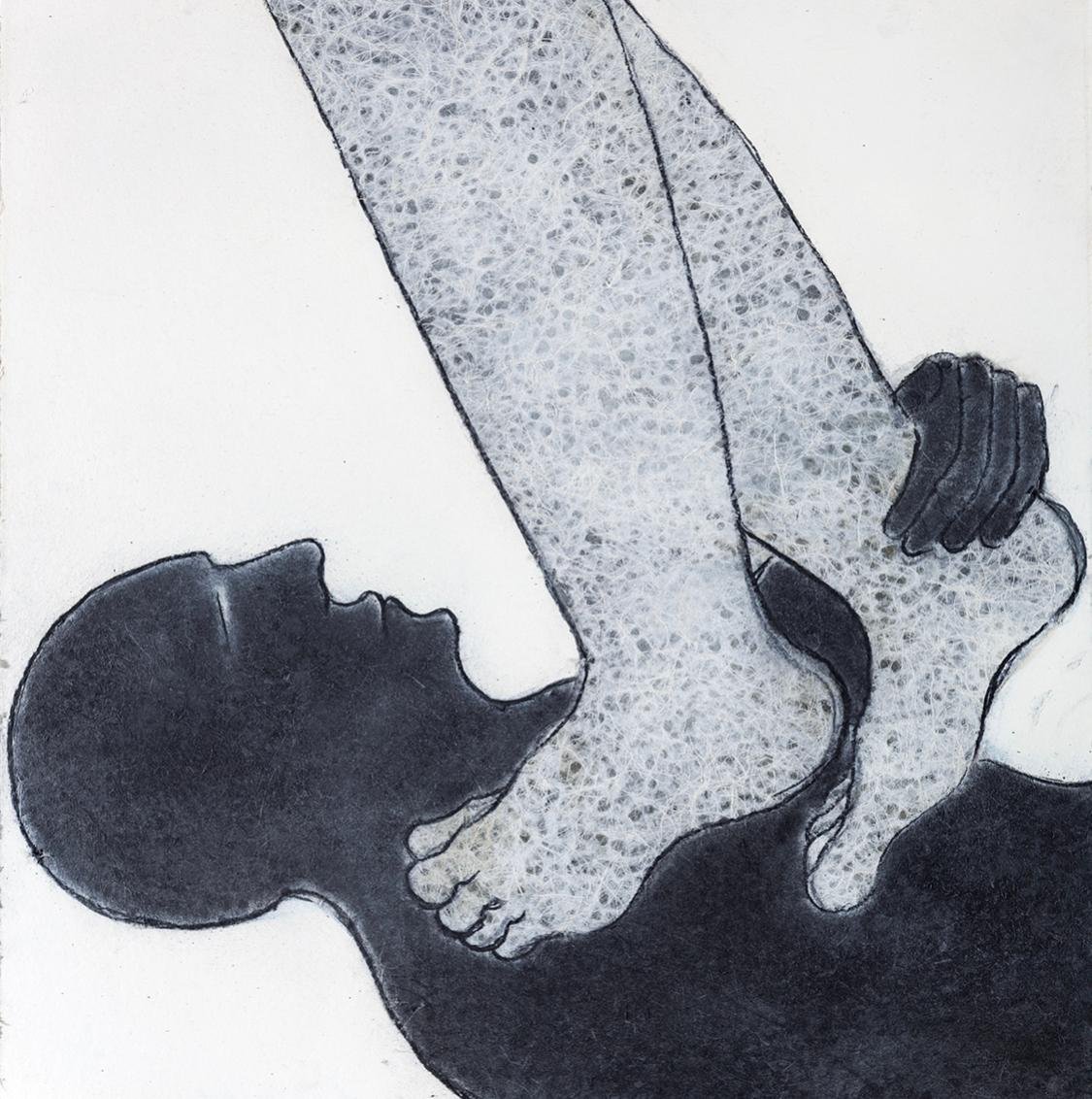

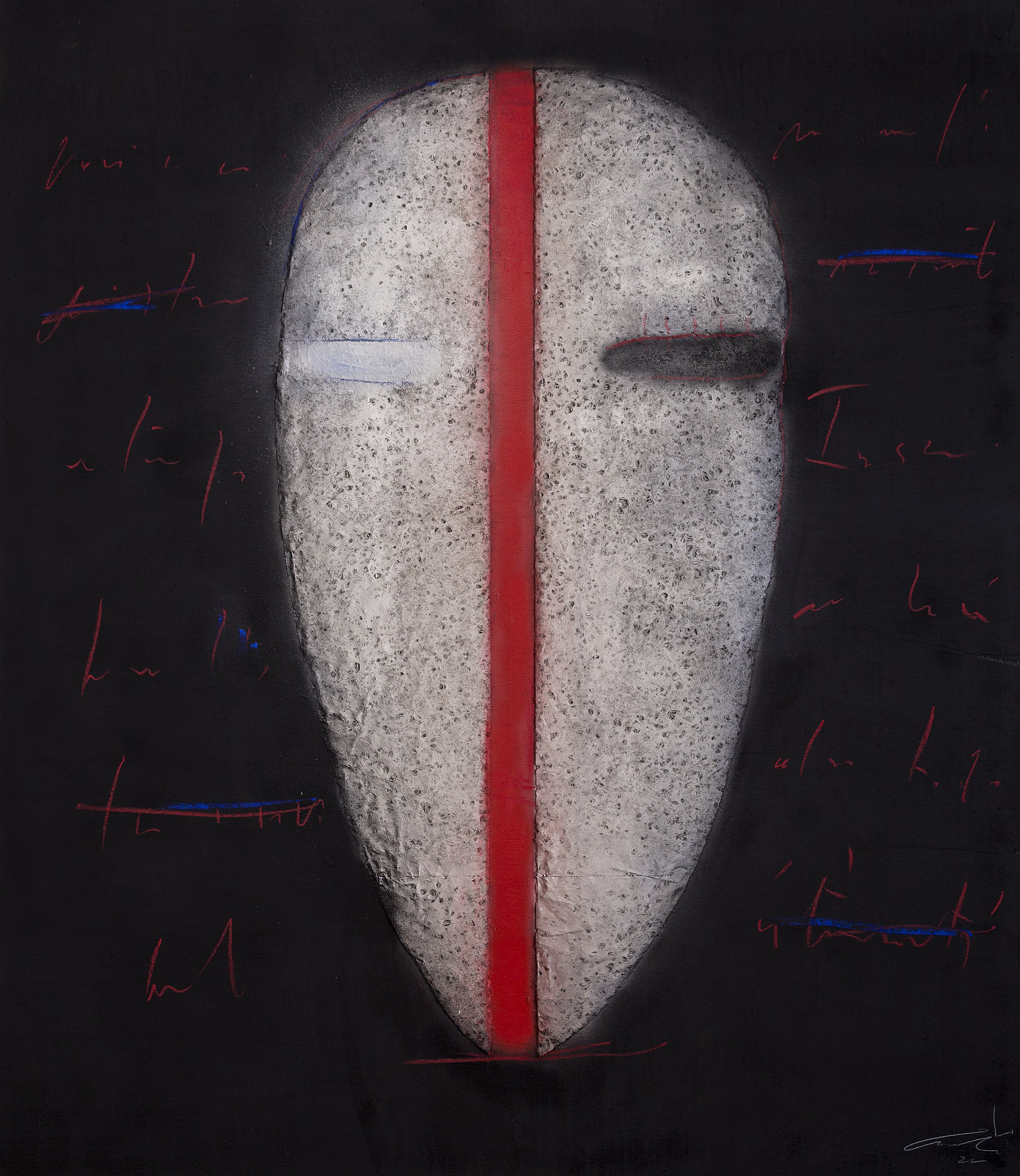

Drawing is foundational to Binebine’s practice as a process of aesthetic formation, one dually rendered through the plastic lines of his masks and portraits and the re-drawing of historical narratives. A hybrid between a careful gesture and a paragon of geometric precision, no two of Binebine’s untitled masks are identical. Reflecting Binebine’s interest in drama and Shakespeare, his masks are like actors who take center stage; in the background, the set juxtaposes home, history, and something in between. Outlined like etchings, marks are a method of individuation: short strokes act as eyelashes framing absent eyes; long vertical lines cross over a closed mouth; other lines form a grid that obscures individual identity. Gestural handwriting appears in select backgrounds as insights into stories waiting to be told. Lines coalesce into contours of feeling, indicating emotions and their development—despair, anguish, grief, and more.

While drawing can embrace a three-dimensional quality, as seen in the way Binebine’s masks rise from their wood background, its form can also be translated into sculpture. Across media, the masks share an elongated outline, and other features further connect them, like a hand. Such a gesture, like the line itself, is multivalent: the raised hand that demands silence; the hand which forcibly silences; a bodily response to shock or woe; or the hand which fosters a gentle embrace.

As the mask takes form through drawing or sculpting, such gestures become metaphors for the processes of identity formation, subjugation, and erasure as they are shaped by abstract and evolving historical trajectories of political subjectivity and social change.

III. Drawing history

Playing with theme and variation, Binebine’s work also draws history as a cycle of oft-recurring events composed of accumulating moments. The Moroccan history Binebine responds to exemplifies this. After Morocco gained independence from France in 1956, King Hassan II took power in 1961. His regime prohibited dissent and silenced critics, including Binebine’s brother. Mohammad VI acceded to the throne in 1999, which some thought would herald a more “democratic” Morocco while many remained suspicious. Indeed, many promises for reform went unrealized (3). This stagnation, among other events, contributed to a contentious situation that culminated in, for one, the so-called “Arab Spring” of 2011 where Moroccans reiterated demands for political reform. Problems, promises, and protests unfolded, and parallels came to light in hindsight.

Binebine’s return to the mask further illustrates these cycles and relationships. The artist first engaged with the subject in 1987–88, and exhibited his work in New York in 1993. While this reconsideration might be interpreted as a direct commentary on Morocco’s politics, this view alone omits a larger universality embedded in the work. Depicted in an ambiguous visual context, the masks are malleable, proposing that numerous histories and experiences fit within the contours of Binebine’s family experience as it was shaped by political events.

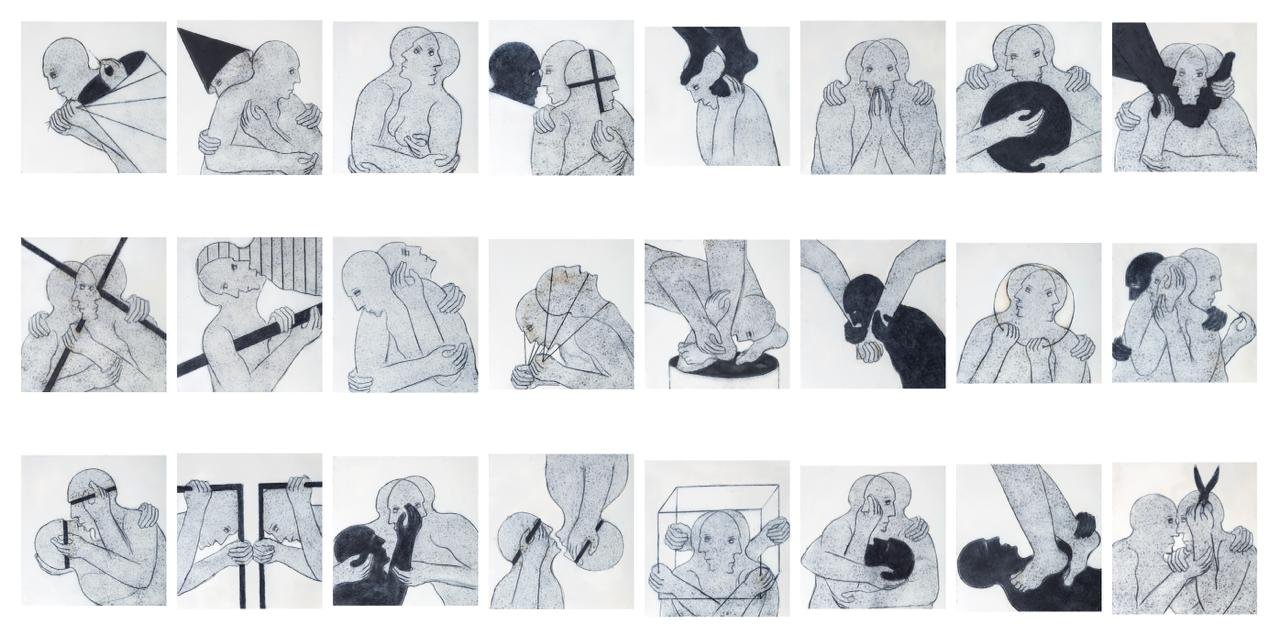

Such inquiries similarly take shape in Binebine’s recent series of 24 untitled drawings featuring duos or trios in profile, each a vignette in an interconnected metanarrative referencing the same historical arc. The subjects are now rendered with geometric precision—a homage to his study of mathematics. Arthur Debsi aptly noted that Binebine’s figures seem “imprisoned by the lines”; their shape confines them and binds them to others (4). Instead of portraits, the artist depicts archetypes of individuals enduring hardships. Challenges are represented symbolically: a box stands for confinement; the scissors, like the individual standing on another’s chest, signifies oppression. The overlay of faces and bodies points toward intersecting experiences. And hands recur in all their polysemy—holding symbols of their oppression, enacting constraints, admitting defeat, seeking protection, and reaching for a tender embrace.

In Binebine’s work, repetitions and relationships are not accidents, but references to the very history we continually reflect on and play a role in drawing.

IV. Drawing connections

Where the lines and contours touch and overlap is the careful crux where Binebine draws connections between individuals, families, and experiences. These relationships are only deepened through repeating symbols and forms that sketch an entangled view of history and family. Yet in the ties that bind, what the artist presents for contemplation is the complexity of the self—perpetually drawn, erased, redrawn, and broken in relation to the other and society. Binebine’s distinct approach simultaneously generates windows into other experiences and mirrors through which we can see ourselves in this narrative—or a vantage point from which to peer into a past that could become our future.

- Rachel Winter

Michel Butor, “An Entanglement of Solitude,” in Mahi Binebine (Morocco: Les Éditions Art Point, 2013), 69.

Katrin Schneider, “Portrait of the Artist as a Painter and Writer,” Qantara.de, February 22, 2007, https://qantara.de/en/article/portrait-mahi-binebine-portrait-artist-painter-and-writer/. Aziz Binebine’s story is also explored in Tahar Ben Jelloun’s novel This Blinding Absence of Light (Das Schweigen des Lichts).

See: Anouar Boukhars, Politics in Morocco: Executive Monarchy and Enlightened Authoritarianism (London; New York: Routledge, 2011).

Arthur Debsi, “Mahi Binebine,” Dalloul Art Foundation, last modified unknown, https://dafbeirut.org/en/mahi-binebine.

About Artist

Mahi Binebine is a painter, sculptor and writer. Born in Marrakech, Binebine lived in Paris and New York before returning to settle in Morocco. His pictorial work, centered on the human figure, evokes the violence and tensions of the Eastern and Western worlds and the tragic situation of human beings. A major painter of his generation, Mahi Binebine constantly explores the issue of humanity and extreme conditions. His figures, reduced to silhouettes, intertwining and colliding bodies, are locked in but undefeated. They inhabit a hostile and troubling world. Influenced by artists such as Goya, Picasso and Bacon, Mahi Binebine constantly explores the strength and dignity of the human beings who face horror and despair. His work has been shown in London, France, Germany, and the United States. It has been noticed by important art critics and is part of numerous public and private collections, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York; Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris; Museum of African Contemporary Art, Marrakech; Kinda Foundation for Contemporary Arab Art, Riyad, Saudi Arabia; Kamel Lazaar Foundation, Tunis, Tunisia; Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul art Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon; Marrakech Museum, Marrakech, Morocco.

About Curator

Rachel Winter is the Assistant Curator at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, and an art historian of modern and contemporary West Asia and North Africa. Winter recently curated the major exhibition Blind Spot: Stephanie Syjuco, which was supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art, and Kayla Mattes: DOOMSCROLLING, the artist’s first solo museum exhibition. She also co-edited Samia Halaby: Centers of Energy with Elliot Josephine Leila Reichert, which will be published in March 2024, and is curating the accompanying exhibition Samia Halaby: Eye Witness, which opens at the MSU Broad Art Museum in June 2024. Winter writes broadly about modern and contemporary art from the SWANA region, American art, and museums.