THE SCAPEGOAT

Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer (US/Italy)

January 9 - February 15 , 2025

Emma Ferrer left NYC in 2021 for Italy and set up her studio in a rural area of Tuscany awash with natural beauty, the palpable influence of Renaissance and Medieval painting, and solitude. Ferrer returns to New York in 2025 with a poignant body of work that looks at the complex and fragile relationship between man, animal, and Nature. The granddaughter of Audrey Hepburn, Hepburn Ferrer has kept a modest public profile over the past decade with select public appearances and philanthropic efforts. This is her first solo presentation.

At the core of this body of work is the myth of The Scapegoat which Ferrer sees as a foundational tale of animal sacrifice that explores common emotions across traditions. The idea for this body of work was born when Ferrer was first exposed to an ancient Greek human-Scapegoat concept whilst studying the Iliad under Gregory Nagy and Kevin McGrath at Harvard. The story of the Scapegoat has since continued to deeply move her as both a very ancient and poignantly contemporary fable.

From pre-biblical and Paleo-Christian myths up until present day stories, Ferrer has found common currents of The Scapegoat in a multitude of unexpected places: among them for example the glorification of racing, la corrida, and hunting practices. To bolster this research, Ferrer has taken a number of courses in Greek mythology, theology, and philosophy of religion at the Harvard Extension School, and currently at Oxford University.

Ferrer speaks about the emotional charge of her own works representing sacrificed animals: “I am keenly interested in complex emotional states of humans surrounding animal sacrifice… among them guilt, grief, regret, shame, hope, ecstasy, catharsis, redemption, and fear of exile.” Ferrer has been reading the works of Sir James Frazer, Kenneth Burke, and René Girard that give a philosophical and theological context to the idea of the “Scapegoat”. She is especially moved by Kenneth Burke who writes, “if one can hand over his infirmities to a vessel, or “cause,” outside the self, one can battle an external enemy instead of battling an enemy within.”

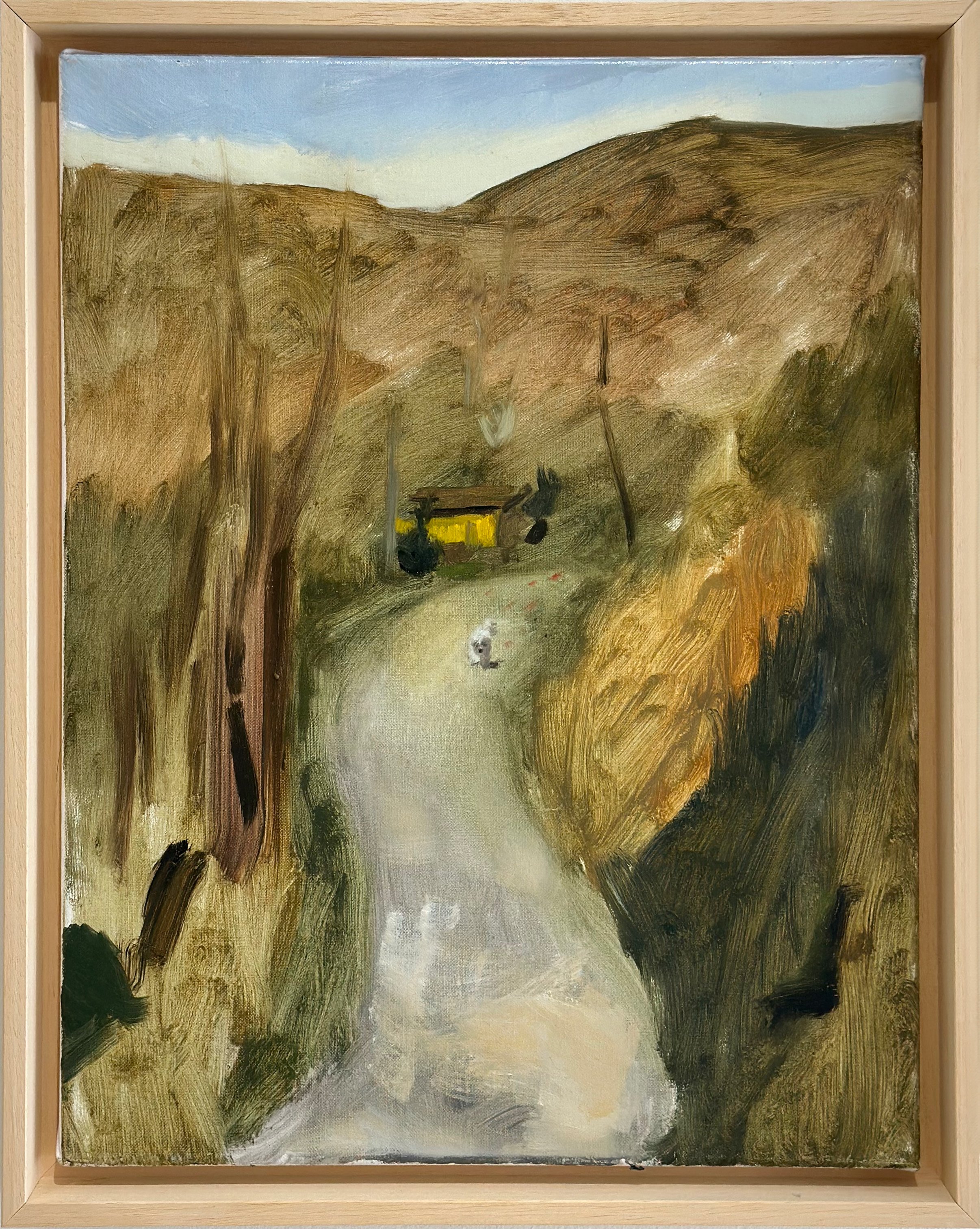

Ferrer, who shares her home and studio in the Apuan Alps with her two herding dogs, Orso and Lilla, also reflects on the various mundane occurrences in her village and community. She is strongly influenced by the profound isolation of her area, and the way that life therein summons a strong interdependence on one’s fellow human and other creatures.

Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer was born in Morges, Switzerland and grew up in Florence, Italy surrounded by the works of medieval and Renaissance artists. As a young adult, Ferrer spent six years in New York where she maintained a studio practice whilst working in art galleries as a curator and artist liaison. In 2021 she returned to her home in Camaiore, Italy, devoting herself to her art practice. There, reflecting on the remote beauty of her rural environment, she began investigating a complex relationship between humans, animals, and Nature, and the relationship of these to a higher power. This new body of work that looks to pre-biblical & Paleo-Christian myths up to present day narratives around animal sacrifice will be exhibited at Sapar Contemporary in 2025.

Early in her artistic career Ferrer pursued a classical education in drawing and painting. One of the youngest students ever accepted into the academy, at 18 years of age she enrolled in the Advanced Painting program at the Florence Academy of Art, a traditional atelier where she would be imbued in the techniques, methodologies, and theories of the old masters. There, Ferrer undertook exhaustive studies from life including still life and the live figure, studying human anatomy as well as becoming fluent in classical materials in drawing, painting, and sculpture. While she initially honed in on an extremely naturalistic way of portraying reality, working solely from life, Ferrer over the last decade has looked inward, greatly loosening her style and leading with an emotive and intuitive practice.

Ferrer received her MFA from Central Saint Martins in London in 2024. Throughout the course of her education she has studied under and worked for artists such as Golucho and the maestro Ivan Theimer. She has curated the works of fashion designers Zac Posen and Manolo Blahnik, and artists such as Eugenio Pardini and Sofia Cacciapaglia. Ferrer holds significant admiration for the Quattrocento painters Piero della Francesca, Masaccio, and Paolo Uccello. As a young painter, Ferrer also spent extensive time in Spain where she discovered and began investigating the works of Francisco de Zurbaràn, Symbolist painter Julìo Romero de Torres, and Goya.

Essay by Annabel Keenan

In Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 philosophical tale “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” she wrote of a utopian city, Omelas, that was perfect–no suffering, no strife, abundant resources and constant happiness. It also held a dark secret: the prosperity of the people of Omelas was dependent upon the suffering of another. As infinite as the good fortune of Omelas, so too was the adversity imposed on a young child, forced to live in darkness and despair for eternity. All citizens knew of this sacrifice for their happiness. Some left, but many remained, allowing the child to bear the burden of constant suffering so as to rid themselves of pain.

This child, like so many other characters throughout history, was a scapegoat. In the Bible, the idea of a scapegoat is introduced in which the sins of man are metaphorically poured onto a goat who is then cast off into the wilderness, taking this burden with him. The Bible then says another goat is to be sacrificed. This ritual is central to the Jewish tradition of Yom Kippur and appears again across cultures from ancient Syria to ancient Greece. The details of each story vary, but in all a goat (or sometimes a human) is slaughtered or cast away for the sake of another’s sins.

Today, the trope of the scapegoat endures, though its brutal connotations are not always central to the story. Scapegoats appear throughout popular culture, in movies and TV shows, as well as real life, in particular in politics, as figures who bear the blame of something negative in place of another person. They are also the subject of artist Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer’s first ever solo show featuring oil paintings and one etching, a presentation aptly titled “The Scapegoat.”

Ferrer’s interest in the scapegoat began in college when she was studying the “Iliad” and learned about the ancient Greek use of the term in which a human took the place of the goat. Often referred to as pharmakos, the ancient Greek ritual saw an enslaved person or criminal sacrificed for the greater good, such as to ameliorate a civic issue like plague or famine.

At the same time, Ferrer discovered a painting called The Scapegoat (1854-1856) by William Holman Hunt, which portrays the scapegoat from the Book of Leviticus, an excerpt from which is written on the work’s frame, along with one from Isaiah 53:4 that reads: “Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows, yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.” Holman Hunt depicts the scapegoat with its horns wrapped in the sins of man, symbolized by a red cloth. We see the goat wandering in a desolate landscape containing skeletal remains, perhaps past scapegoats who’ve met their final destinies.

“I became obsessed with it,” Ferrer says. “At first I was drawn to the aesthetic of the work and how it was painted.” Over the next several years, the painting remained in her mind as she lived and worked in New York. During the pandemic, Ferrer returned to Italy where she grew up, moving to a small, remote village in the Apuan Alps. She found herself surrounded by the rich landscape and visual culture of the country, of which religion and religious iconography are central.

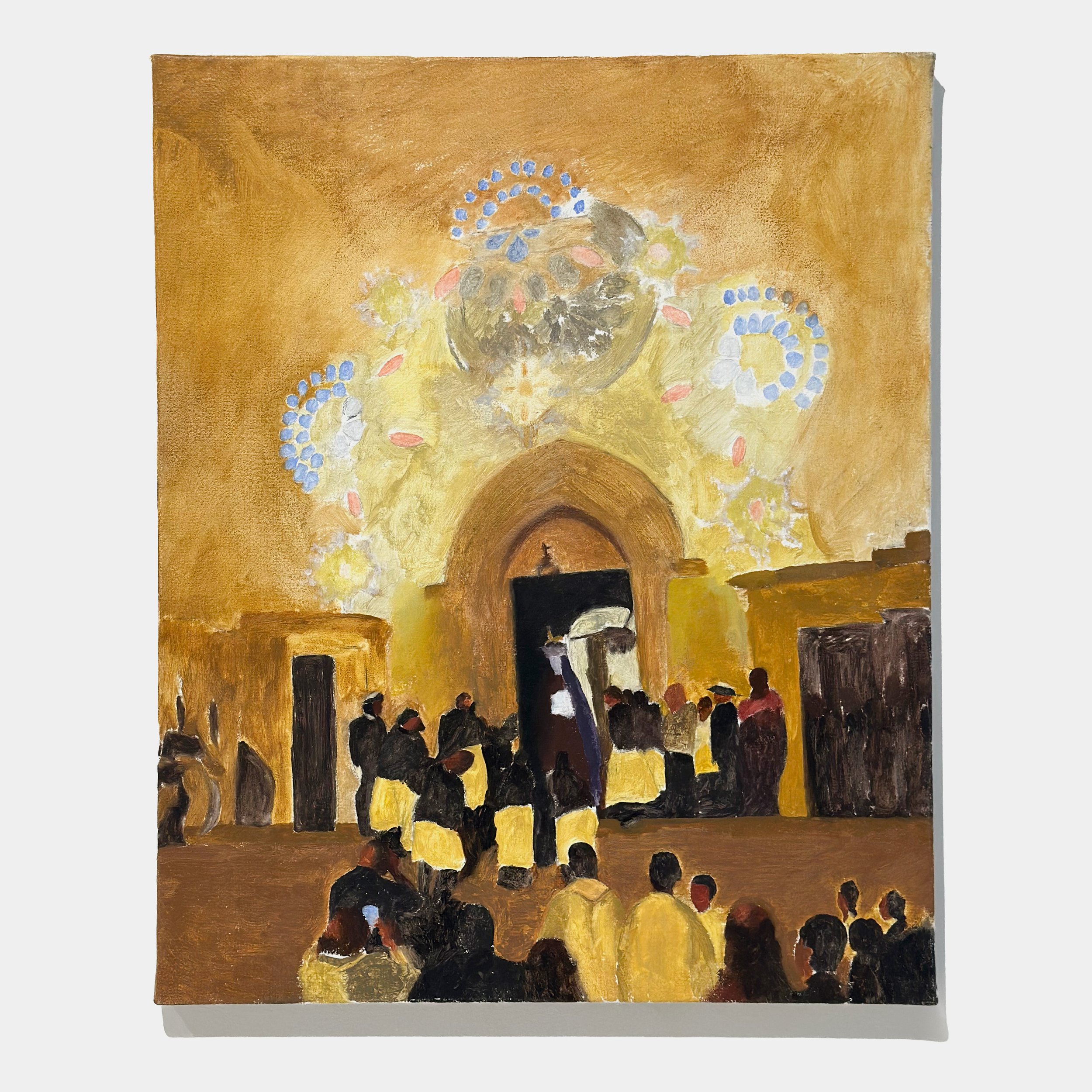

Ferrer began making works about religion and religious processions and objects, but again she came back to The Scapegoat. “I realized that I wasn’t only obsessed with the visual qualities of the painting, but that it represented something much deeper to me, something connected to my spirituality,” she says.

In Ferrer’s own painting titled The Scapegoat, she draws clear inspiration from Holman Hunt. In her work, she portrays a goat in a similarly desolate landscape, but unlike Holman Hunt’s goat, Ferrer’s is lying down as if exhausted or already deceased. It is plump and well-kept. There are no skeletons surrounding the goat–this animal is completely alone.

“There are many different aspects of the myth that move me beyond the metaphorical,” Ferrer says. “The scapegoat is a story of an innocent animal that has been domesticated and trusts humans and is completely betrayed.”

Additional art historical references abound in Ferrer’s show. In Agnus Dei, she depicts a small lamb lying on its side, likely deceased. Inspired by the work of the same subject, which translates from Latin to Lamb of God, by Francisco de Zurbarán, Ferrer’s lamb is untethered and placed upon what appears to be a cushion not unlike a dog bed. De Zurbarán’s depiction, by contrast, shows the lamb with all four legs tied together, a clear sign of man enacting control over the innocent creature. Both Ferrer and De Zurbarán’s lambs are set in a dark, black background, but while De Zurbarán’s serves to add an element of drama and spotlight the white lamb, Ferrer’s frames only the lamb’s head resting softly as if slipping into the darkness that awaits the animal.

Ferrer also draws inspiration from places she’s been, such as Cappella Ospedaliera a Campo di Marte, a hospital where she received treatment and watched a man praying, making her wonder to whom or to what he prayed. Other works recall her life experiences, such as A Humble Return, an image of a dog running down a hill towards the viewer leaving bloody paw prints in its wake, a scene inspired by a similar event Ferrer experienced while walking through the woods with her partner. They later learned that the paw prints were from two dogs who had returned home after escaping and living in the harsh mountains and fighting wild animals for three days. The dogs, descendants of wild species themselves, are as reliant upon humans as are all domesticated animals. Though not an image of a scapegoat, it’s hard not to imagine what it might look like if a sacrificial goat or lamb were to return home.

In another personal reference, At Sea depicts a small lamb on a raft surrounded by a hazy, white sky and sea. The lamb locks eyes with the viewer, its ears sticking out straight as if alert. The subject comes from a dream the artist had in which she watched a small lamb float away on a raft at sea. “The lamb seemed to know me, and I felt like I was responsible for abandoning it; I felt like I had betrayed it,” she says. “I feel that I was carrying a more collective human guilt in this dream, acting as a stand-in for humanity. I felt so empathetic towards this lamb. I watched it get sucked out to sea, and slowly watched as it moved in towards a massive wave, knowing that its end was nearing.”

Ferrer has also begun to explore her own religious practice in her work, one that she calls personal and not tied to a denomination. “In Holman Hunt’s work, I look at that goat and I think about its final moments and wonder whether God is present for the animal,” she says. “The spiritual element of The Scapegoat became an important question for me. Man has taken the animal and exploited it in the name of God. Where is God in this story? In some ways, I feel an emotional obligation to tell the scapegoat’s story and to depict the trifecta of man, animal and nature. Nature can also be synonymous with God.”

With this last point, Ferrer references the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who posited that nature and God are one. In this light, God might be interpreted in the natural settings of Ferrer’s work. Perhaps her depiction of the scapegoat in the eponymous painting is not alone after all. Perhaps God is in the landscape, or perhaps he is somewhere else, present, but not seen.

Though personal interests and motivations drive Ferrer’s practice, her inspirations are collective and multicultural, opening them to different interpretations depending on what the viewer brings to the work. “The scapegoat can be a metaphor for a million and one things, and I can’t say that I’m drawing from one specific metaphor,” Ferrer says. “My work is about the incredible capacity for cruelty in man, and how this manifests in his relationship with nature and with animals. I want the viewer to reflect on the experience of the goat. Whatever this means is up to them.”

About Annabel Keenan

Annabel Keenan is a Brooklyn-based writer specializing in contemporary art and sustainability. She contributes to several publications, including The New York Times, The Financial Times, The Art Newspaper, Artforum, and Brooklyn Rail. She is also the author of the forthcoming book Climate Action in the Art World: Towards a Greener Future, a call for sustainable practices in the art world, which will be published May 2025 by Lund Humphries and Sotheby’s Institute.