Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia):

Ancient Myths and Personal Stories

Essay by Elena Pakhoutova,

Senior Curator, Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art

September 8, 2023 - October 10, 2023

Opening September 8, 6-9 pm

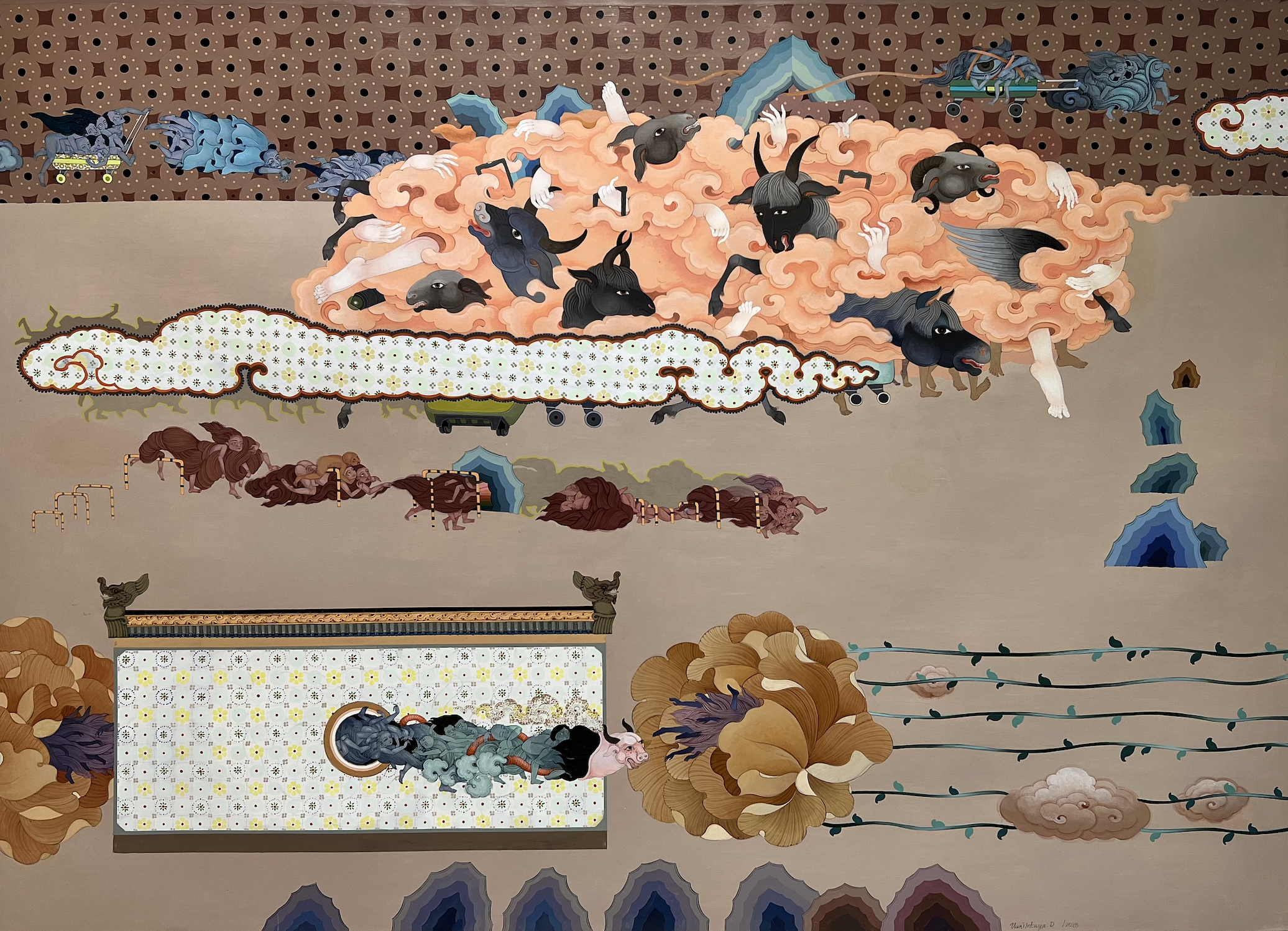

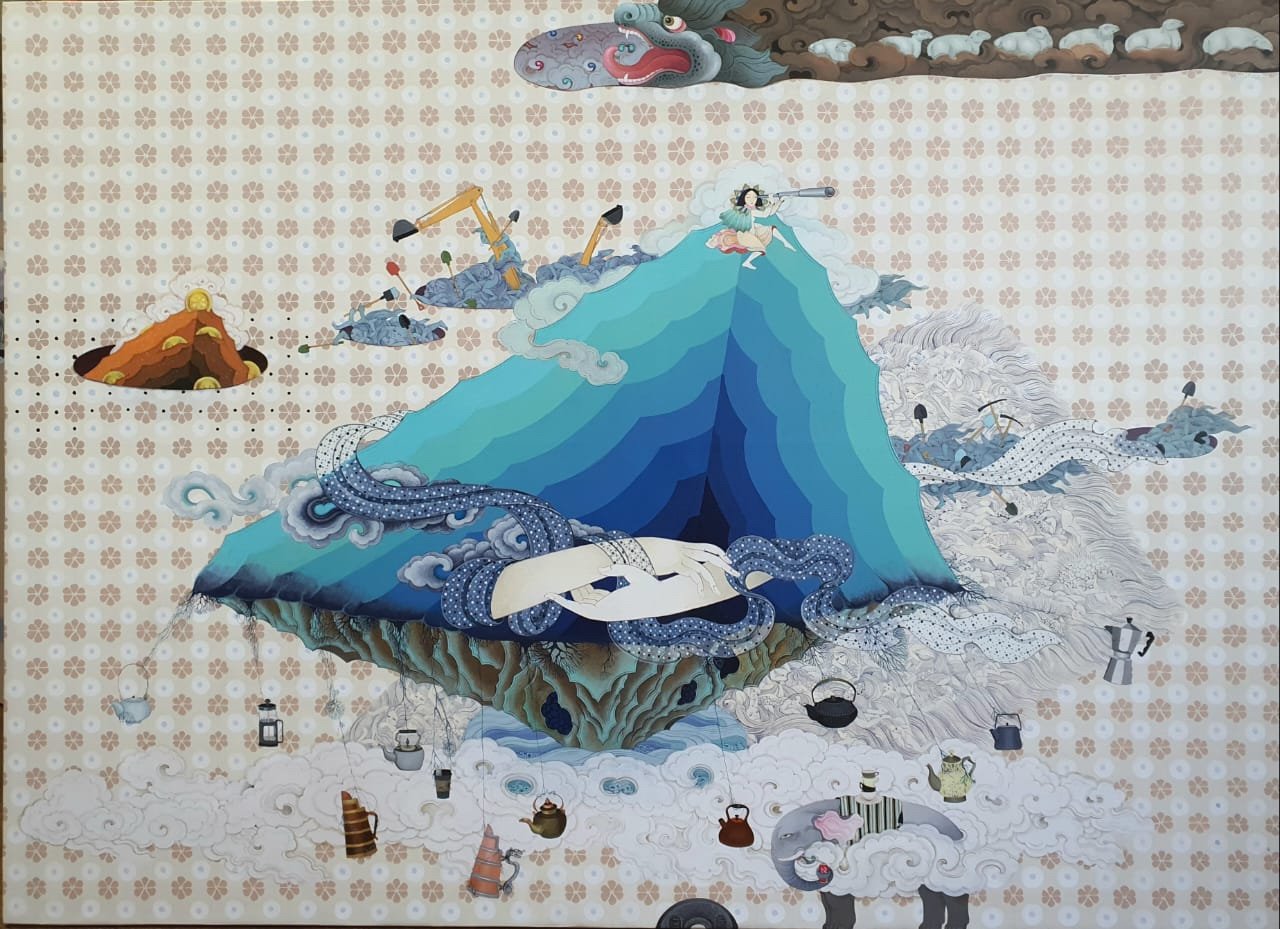

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu’s (Uuree’s) painting style is distinct and immediately recognizable as she blends elements of Mongol Zurag, Tibetan Buddhist imagery, and Asian miniature tradition with contemporary figuration and surrealism. Her visual vocabulary draws from Buddhist and Mongolian folk traditions, but also from images associated with technology, social media, games, avatars, blockchain and metaverse. Uuree’s compositions are full of intimate and relatable details of her own life. However, the artist’s narratives are never linear, but mysterious, associative and open-ended. Uuriintuya creates a personal cosmology where universal and personal, real and imaginative, dreamlike and mundane, historical and contemporary exist together.

The Life and Liberation of Traditional Symbols in Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu’s New Paintings

by Elena Pakhoutova, Senior Curator, Himalayan Art, at the Rubin Museum of Art

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu’s paintings may evoke different and divergent thoughts in the viewers who are enjoying them. Such personal impressions depend on these observers’ own interpretations of what they see, the specific features their eye and mind get attracted to and follow on her canvasses. These captivating details can be, for example, the black birds that seem to merge with figures whose hair resemble birds’ wings, all tangled in a nest-like tree. Bright orange/ochre scarves flow around these beings and the birds unify them into a composition while only one bird seems to be escaping this “nest”. In traditional Buddhist hanging scroll paintings (thangka), the black bird, or the raven, is the symbol of the Buddhist deity Mahakala, the state protector of Mongolia. The scarves here are nearly a direct quote from traditional Buddhist painting in which similar flowing scarves billow around the arms and bodies of deities. For me, in the Uuriintuya’s painting the scarves imply that the tangled beings in the nest are significant, even though they may not be the central focus of the painting. By the artist’s admission, when she uses elements from traditional Buddhist paintings, she liberates their symbolic iconography and often imbues them with her own meaning. Still, even transferred to Uuree’s visual stories, the symbols retain their meaning in their form.

In one painting, which compositionally and formally parallels images of the Buddhist thangka paintings, a scarf billows around the central figure of a standing woman in armor. To me this signifies the authority of that figure who stands on a floating rocky pedestal, which is supported by a flower. Notably, this flower is not a lotus but edelweiss, the flower of Mongolian steppes and highlands. In this painting in particular, traditional iconographic elements—a round body halo of the figure (mandorla), a halo around her head with the wind-swept hair, her gestures (mudra), and the lotus flower held in her left hand—suggest this figure to be Avalokiteshvara, or Chenrezig, the lotus-holding bodhisattva. In Tibetan Buddhism, this deity is usually depicted as a male, although in canonical texts such beings are rather gender neutral, not clearly defined as either male or female. Responding to my query about the feminine appearance of this figure the artist said that the change was intentional, as gender is a social construct and varies in different times. Similarly, in the painting that evokes images of Buddhist protector deities, a female figure stands on a lotus pedestal. The word security is printed on her black t-shirt and her armor seems to be covered by a corset. The artist mentioned that in her interpretation, the lotus signifies not only the idea of purity and rebirth but authority. The elements of Buddhist iconography also signify authority of this figure and her power to protect.

Another evocative and persistent motif which inevitably draws my attention are the colorful clouds, which often serve as a setting for her numerous whimsical vignettes. For many, the clouds would be a reference to the sky, but in traditional Buddhist paintings they could also represent another plane of existence, an elevated state, or signify distance from the present and more. Unsurprisingly, all these meanings seem to fit Uuriintuya’s paintings. Her clouds accommodate the existences of her thought forms, the constructs from her mind informed and directly inspired by her present-day experiences and objects. Abstracted and presented on this new plane of her imagination’s reality, her clouds take intentional shape on her canvases. Or, as if taken for a closer observation, mixed up in a dream-like form, they make up a larger part of a body filled with various versions of emotional states (of being), depicted as human figures hiding in the clouds that swirl within the confines of the larger human form.

Though Uuriintuya claims she does not intentionally encode the traditional iconographic elements with their symbolic Buddhist meaning and uses other traditional elements that reflect cultural sentiments absorbed into her very being—snow lions, makaras (mythical crocodile-like creatures) on portals, or flowers, rocks, and trees—which may appear decorative, all these symbols create another, deeper dimension to the artist’s stories communicated in the paintings of this new body of work.

About Curator

Elena Pakhoutova, Senior Curator, Himalayan Art, at the Rubin Museum of Art holds a PhD in Asian art history and criticism from the University of Virginia. Her background in Tibetan Buddhist studies informs her interdisciplinary approach to art history and curation. At the Rubin Museum, her thematic exhibitions introduce and contextualize Tibetan, Himalayan, and Nepalese art. Her 2019 exhibition The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel brought together traditional and contemporary works of art and deconstructed core Buddhist concepts with contemporary new media, immersive and impermanent art. Her current cross-cultural exhibition Death Is Not the End explores death and afterlife through the art of Tibetan Buddhism and Christianity. She is co-leading (with Dr. Karl Debreczeny) the Rubin Museum’s Project Himalayan Art, which launched in February 2023.

About Artist

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (b.1979) is a contemporary master of the Mongol Zurag painting, and is widely respected for her innovations in this style. She notably integrates traditional Mongolian and Buddhists motifs with contemporary themes, as she chronicles the lives of women and everyday, mundane life across the seasons in her post-nomadic homeland.

She began exhibiting as a student since 2001 and had solo exhibitions in Ulaanbaatar in 2006 and in 2018. Dagvasambuu participated in group exhibitions at home and internationally including exhibitions in Las Vegas (2006), Beijing (2008), Hong Kong (2011), Fukuoka (2012) London (2012), and Düsseldorf (2012). She has also participated in the Shanghai Bienniale (2012), the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennial (2014), and the Asia Pacific Triennial (Queensland, 2015). Dagvasambuu was also a part of the 2017 Documenta 14 tour.

Her works are included in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art, Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, Smith College Museum of Art, Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, Queensland Art Museum in Australia, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan.

Dagvasambuu’s development of traditional motifs and pictorial language into unique representations of Mongolian women amidst the rapidly changing life in the 21st century has been recognized in her home country. Her works were selected for the 2013 Grand Prix for Best Artworks of the Year from the National Modern Art Gallery of Mongolia for the 2018 Grand Prix for Best Artwork of the Year from the Union of Mongolian Artists. Dagvasambuu graduated from the Institute of Fine Arts, Mongolian University of Arts and Culture. She currently lives and works in Ulaanbataar.